Civil War & The Battle of Stamford Hill, Stratton

Charles 1 after Van-Dyke

If you have read the Sir Bevill Grenville story on this website, you will have seen how Charles 1 had assumed the same style of monarchical power as his father James 1 of England, V1 of Scotland. He believed in the “Divine Right of Kings”, that monarchs were appointed by God. This brought him into conflict with a Parliament which felt it should have many of these powers and to raise taxes; on 1 June during the Long Parliament, the Members published “the Nineteen Propositions”, a document that stated its demand to limit the King’s power. These issues had also become conflated with Catholicism, Protestantism and whom the King should marry and so much more. Also, as you may have read, one of Bevill Grenville’s long-term friends was one of the main protagonists arguing the Parliamentary cause.

It was a time when there was a desire by many leaders for a new form of governance. But equally for many others, the power of the King was absolute and could only function if the powers of State followed down from the King to the people, or through the bishops, to the church and then to the people. Destroy these structures and you destroy the whole edifice of governance.

However, for both King and Parliament deciding to fight over these issues was not a simple matter of declaring war. Both factions had to raise an army. There were effectively three ways this could done. Parliament could call on the Deputy Lieutenants for each county, who were responsible for raising and supporting trained bands of militia - Parliament had the power to appoint Deputy Lieutenants but not all would necessarily agree with their cause. A second option was to obtain the support of the Sheriff of the County who could call upon the “passe comitatus” which included all men of fighting age in the county. But again, the Sheriff could decide on which side the county fought. And these men were not trained soldiers.

A third option was for the King to issue a “commission of array”, sending officers so commissioned to go into the county to muster its inhabitants. The commission of array was issued under the Great Seal of England and was more authoritative than anything requested by Parliament, and this would prove important in Cornwall. (Image shows the Great Seal of Charles 1st.)

The Cornish were easy to antagonise if they were losing what they held dear, such as their religion or language, but they were essentially law abiding. The powers of the King were sacred rights and could not be countermanded.

The King ultimately decided war was inevitable and commissions of array were despatched on 11 June 1642 and the commissioners for Cornwall were Sir Bevill Grenville of Stowe, his cousin John Arundell of Trerice and Ebbingford and John Grylls the County Sheriff and they set about raising the funds and training the men for the impending battles.

The King finally raised his standard at Nottingham on 22nd August 1642 and a state of Civil War existed but, as yet, he had no professional army at his command.

For the majority of Cornish gentry and its people, they understood the issues and may well have agreed with them, but for the Cornish the King’s writ must hold, and most came out on the Royalist side, often with much encouragement from their local landlords and gentry.

Beyond the river Tamar, things were not so clear. Bevill Grenville’s own manor at Bideford, in Devon, came out in favour of Parliament, as did Somerset and many other parts of Devon, and there were Parliamentary supporters also in southeast Cornwall.

Letter from General William Waller, Parliamentary leader to his friend Sir Ralph Hopton, the King’s Commander in the West.

It could be argued that the Cornish Royalist’s mindset was to clear the county of Parliamentary forces and put up the barriers along all Tamar bridges. They did not want to fight a Civil War outside the County; it did not play out that way, of course, but they would try, and it could equally be said that they were correct in that judgement as most ventures beyond the Tamar ended in a retreat back into Cornwall.

The fact is that the Royalist commanders did not know on whom they could rely in Devon to support the incursions outside of Cornwall. Most of the Royalist supporters were in southeast Devon and, Plymouth and Tavistock, stood in the way.

Of course, the divisions were not just between counties and regions but also between families and friends and some changed sides during the conflict. This did cause great anguish for all; letters we have are of heartfelt despair; that they would have to meet their long-term friends across the battle fields. The sentiment was one of resignation, that this had to be fought out, resolved and then, hopefully, friendships would be restored.

The inter-family anguish, the dilemma, the soul-searching for everyone is most pronounced in a letter between two brothers, as they faced the question of the powers of the monarch, countered by the need for greater accountability with laws and taxes decided by elected members of Parliament.

The letter is between Edmund, son of Sir Ralph Verney and his brother which encapsulates this anguish; the first lines of which reads:

“Brother” what I feared is proved true, which is your being against the King. Give me leave to tell you in my opinion tis most handsomely done and it gives my heart to think that my father and I, who so dearly love and esteem you, should be bound in consequence – because in duty to our King – to be your enemy. I beseech you consider that his Majesty is sacred; God saith, “touch not mine anointed”.

This was the essential dilemma for many; they believed that the Kings wishes, his command, could not be countermanded. For Bevill Grenville he had previously written:

“I cannot contain myself within my doors when the King’s standard waves upon the field. For mine own part, I desire to acquire an honest name or an honourable grave. I never loved my life or ease so much as to shun such an occasion”.

Sir Bevill and his Cornish leaders by Robert Lenkiewicz

Sir Bevill held the King’s commission, and he had the personality, and most of his local people were loyal followers; he was going to lead his Cornish men in a fight for the King.

However, he was not only prepared to put his life on the line for his King. To finance his army, he mortgaged Stowe Barton and the manors of Kilkhampton and Bideford. And he sold his two mills at Coombe and Stowe Wood. Plus, he sold a lease he held on a property at North Leigh in Devon. In one way or another he had borrowed £25,000 and he would have great difficulty in ever being able to pay the instalments.

He was not alone in trying to raise funds. Parliament was scanning the country for plate and silver to melt down for coins and Queen Henrietta Maria went off to Holland to, “sell the family silver”.

Despite these difficulties, during the winter of 1642–3, Sir Bevill Grenville, Sir Nicholas Slanning, John Trevanion and John Arundel – raised a force of over 1,500 infantry that became the nucleus of the king’s Western Army. And Bevill had managed to have manufactured and stashed away around one thousand pike ready for men to defend themselves – not to mention, one presumes, some level of armour.

The Parliamentary forces were also actively setting up their supporters. In Cornwall, Sir Alexander Carew of Anthony, and Sir Richard Buller of Morval, were both active parliamentary committee men, and Sir Richard was also the member for the county. They both declared for Parliament. They possessed themselves of the eastern part of Cornwall and placed garrisons in Launceston and Saltash; parliament thought they had secured the whole county- excepting Pendennis castle, whose governor, Sir Nicholas Slanning, was a zealous royalist.

So, this was the situation during the lead-up to war. However, whilst it played out in all parts of the realm, this account can only discuss the events in Cornwall, with particular emphasis on the actions of Sir Bevill Grenville of Stowe and how local people were involved.

Ultimately, the story leads to the battle at Stamford Hill, Stratton on Tuesday 16th May 1643 and the following fateful battle at Lansdowne Hill, Bath, 5th July 1643 in which Sir Bevill Grenville met his “honourable death”.

The image shown is of of Sir Bevill Grenville, after Van Dyke; rather formal but perhaps portraying Grenville’s own characterisation of “ acquiring an honest name or an honourable grave”

To make this account easier to follow, each manoeuvre, muster or battle from around July 1642 to June 1643 is supported with maps or images.

The story thus starts on the 18 July 1642 when William Seymour, Marquess of Hereford, sets off for the West Country. He carried with him the King’s Commission as Lieutenant-General of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, including Bristol, Exeter and Poole. He was accompanied among others by Sir Ralph Hopton. The Marquess had written to the Queen that very day saying:

“I am with all speed to repair unto the West to put my Commission of Array in execution, which I mean to perform without difficulty”.

Events did not unfold that way. He got driven out of Dorset and, no doubt, elsewhere and by September of that year had ended up in Minehead where he jumped on a Collier returning empty to South Wales; basically, he absconded.

The Marquess had made Sir Ralph Hopton Lieutenant-General of Horse in the West, but little else. With him were Sir John Berkeley, Colonel Ashburnham, Sydney Godolphin, some officers, 100 horse and about fifty dragoons. This was September 24, 1642. Hopton decided to make for Sir Bevill Grenville’s manor at Stowe.

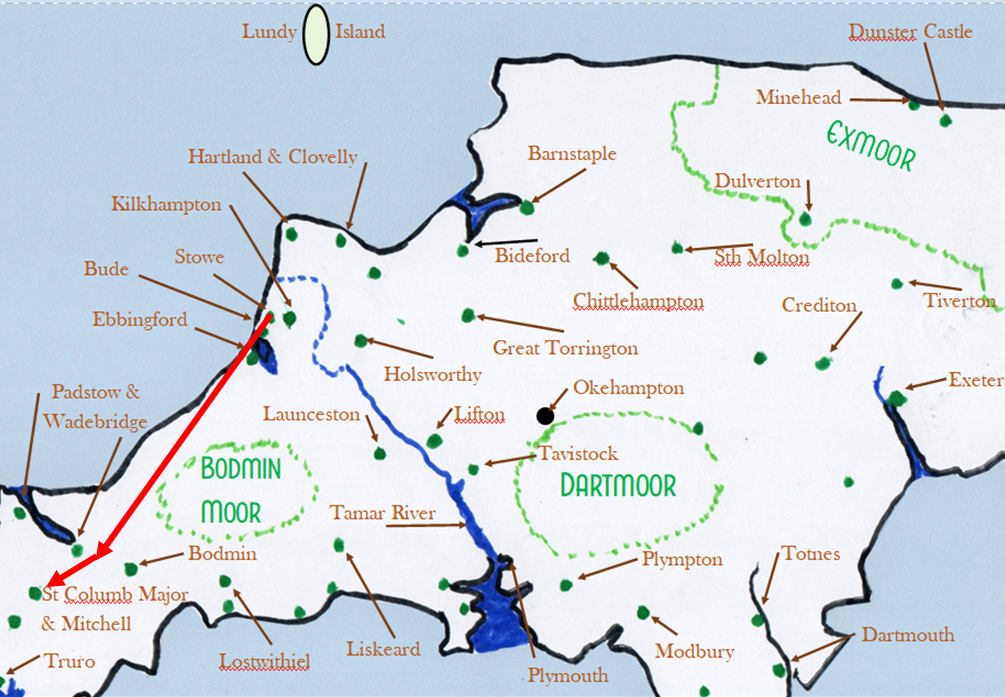

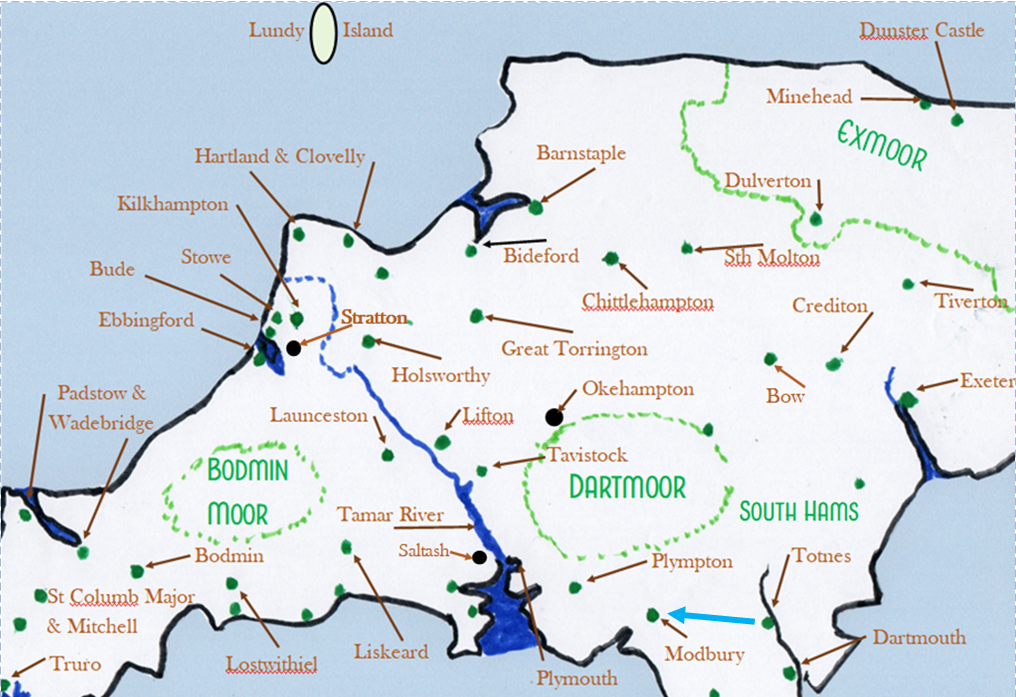

The map shows the route, marked in red, that they were forced to take to avoid Parliamentary Roundheads and their sympathisers in many of the Devonshire towns. Which necessitated engaging local guides. Around 75 miles of riding later saw a very tired military contingent passing down through Kilkhampton and on to Stowe.

For Bevill’s wife Grace, this must have been quite a task to accommodate the leading officers and arrange provisions for so many. They were bound for Pendennis Castle, Falmouth where the Governor Sir Nicholas Slanning, was a strong Royalist and where there were munitions and room to accommodate a small army and plan strategy.

The logic of heading to Cornwall was very sound. It was comparatively easy to defend, with the Tamar separating the County from the rest of England; and Devon had too many Parliamentary supporters for comfort.

Cornwall, by comparison, had forty-three gentlemen, seven thousand esquires, freeholders and others who had petitioned for the King in York, June of that year.

A long stay at Stowe was out of the question. The Parliamentary spies were everywhere and soon Sir Richard Buller, a Roundhead leader, then at Saltash, heard about Hopton’s arrival in Cornwall and issued orders for the militia to gather at Bodmin on the 28 September.

The Royalist departed Stowe on the 27 September, accompanied by Bevill and his men and they made their way through Stratton and Wadebridge to St Columb Major. Where almost a thousand foot had been gathered. (See map with route in red.)

It is highly probable that this build-up of men was the work of Sir Bevill and his network of relations. Sir John Arundell of Trerice lived nearby. These men would by now have been equipped with Grenville’s stock of pike and represented a significant challenge to Buller’s men.

It would appear that the commanders of the opposing forces did meet and Sir Alexander Carew, a Cornish Roundhead, effectively decided to discuss a possible truce at Michell the next day.

So Hopton and Bevill, instead of turning right towards Bodmin and challenging the Roundheads, turned left and headed the short distance to Castle-an-Dinas, which is a large Iron Age fort, and there they camped.

No doubt both forces were very tired from days of marching. The next day the opposing Commanders met at Mitchell, around three miles away, to thrash out the finer details of a longer truce but nothing was agreed.

However, the Roundhead force was free to escape to the east, probably to Launceston and, Hopton sent his Pikemen home leaving the remaining Royalists Cavaliers to head for Pendennis, unmolested.

Photo courtesy of English Heritage.

Sir Bevill’s local knowledge of Cornish procedure, not to mention his many relations and friends thereabout, came very much to the aid of the force at this time.

The Quarter Sessions were sitting at that time at Lostwithiel and a submission had been received charging the Roundhead Buller and his Saltash levies, then at Launceston, with unlawful assembly but there was also a reference to “persons unknown” with the same offence. The “unknowns” were Hopton and Grenville’s men and given that Sir Bevill was unquestionably known by most at the Quarter Session, this does seem a procedural point.

Two of the magistrates presiding at Lostwithiel were Bevill’s friend, William Coryton, and Ambrose Manaton. These two men then proceeded to Launceston to invite the Roundheads to disarm and depart the county- Manaton, as a pacifist, simply wanted to avoid bloodshed; Coryton’s objective was to rid the county of parliamentary forces.

According to custom, the Quarter Session then moved to Truro where many of Sir Bevill’s associates presided in various capacities. (See locations on map.)

When Hopton, as leader of one of the “unknown forces entering the county”, presented the jury with his King Commission as Lieutenant-General of Horse in the West, this carried more weight than anything produced by Parliament. The foreman of the jury thanked Hopton for coming to the aid of the county.

John Grylls, the Sheriff was now free to raise a posse and he wanted to set off for Launceston to drive Buller and his men out of Launceston.

The constables were directed to organise a posse to gather at Moilesbarrow Down on 4 October 1642. Some three thousand turned up. They had been told their wives and children might be at risk unless these unwelcome people were not driven from the county. There weren’t sufficient arms for such a number, but they all set off for Launceston where they bivouacked overnight. (Map Route Taken in Red.)The following morning, they advanced on Launceston but when they reached the town, they found the Roundheads had departed, back over the Tamar into Devon. That October 1642, the people of Launceston were pleased to welcome the Cornish and simply opened the gates for them.

Hopton and Sir Bevill wanted to pursue the Roundheads beyond the Tamar, however, the Sheriff’s remit did not permit him to act beyond the county. Rumours were around of a sizeable force under the command of Sir George Chudleigh, just three miles away at Lifton. However, it was decided not to invade Devon, but to head for Saltash instead and drive all remnants of Buller’s Parliamentary forces out of the county. This was achieved.

With the whole of Cornwall having been cleared of Roundheads, the posse was disbanded and the men sent home. Hopton wanted to raise a sizeable, trained army from within Cornwall. This he judged would be necessary if they were to drive all Roundhead forces out of Devon.

Sir Bevill also held the King’s Commission to raise a whole regiment of foot, and this would undoubtedly have been on Hopton’s mind as he planned the next moves. And many of Grenville’s associates volunteered to raise regiments. These included Sir Nicholas Slanning, the governor of Pendennis Castle- Sir John Arundell having given him permission to leave that post. Also, Colonel John Trevanion of Carhayes and William Gadolphin raised regiments and Captain Edward Cosoworth undertook to raise a troop of dragoons.

Bevill was essentially a man loyal to the local people and to his tenants, but war was a different matter and he expected them to follow his request. He commanded Captain Cottel from Morwenstow to deliver a letter to his wife, Grace, at Stowe in effect criticising those tenants who did not come forward and join this posse. The implied message was blunter, Sir Bevill would drive his tenants out of house and home if they will not come out and assist him and his confederates. It was the duty expected of Grace to disseminate this to the local people.

There now followed a period of consolidation, recruiting and training and planning. Some of the planning appears to have taken place at Stowe as Hopton, Berkeley and Ashburnham now rode with Sir Bevill to Stowe. The plan concluded that the main recruiting and training should take place at Bodmin.

It would seem that Sir Bevill also planned to have some enjoyment at the expense of the Mayor of Bodmin as he asked him to order three gallons of sack. (This, apparently, is a type of fortified wine.)

Image by W. N. Gardiner- Ashmolean Museum.

There was, however, a threat from a group of Roundheads garrisoned at Mount Edgecombe, a peninsular, just to the south of Saltash, a little too close to the home of the Cornish Roundhead Carew. (See Map Route in Red)

By chance Lord Mohun’s new regiment and Captain Cosoworth’s dragoons were nearby and they were detailed to seek them out and push them back across the Tamar. There was some toing and froing of fortune, but the Cornish contingent won the day and Cornwall was, once again, free of Roundheads.

This was the first encounter on Cornish soil between regular trained troops and it was Cornish who came out on top.

The Royalists in Devon heard that Cornwall had dispelled all Royalist forces, and wanting to show their support for the King, invited the Cornish to join them. The idea being that as a large, combined force, they could also drive the Roundheads out of Devon.

However, the Devonshire Royalists were not well informed when it came to knowing their enemy within, as Hopton would more than once discover. Nevertheless, the newly appointed Royalist Sheriff of Devon, Sir Edmund Fortescue, went to Bodmin with his friends and persuaded the Cornish to cross the Tamar with a posse and gather at Tavistock. (Route in red.)

The newly appointed Cornish army eventually crossed the Tamar and marched into Devon on the appointed day, only to find Tavistock garrisoned by a Roundhead force. Fortunately, for all, the sight of such a force arriving at the outskirts of the town, encourage the Roundheads to retreat to Plymouth. Hopton and the Devon Royalist were beginning to discover that the Royalist’s stronghold in Devon was in reality, only to the east, in the South Hams of the County.

However, the Cornish army was well provisioned and financed at this time and they had little resistance as they headed east gathering villages such as Plympton and Totnes to the Royalist cause as they progressed. Plympton was important as the town had been held by a force commanded by General Ruthen. For the moment he too retreated to Plymouth to plan his next move.

The Sheriff of Devon now suggested that it would help the cause if the Cornish moved over to Modbury and join with the men from Devon. Hopton left Sir Bevill and his men in charge of Totnes and Hopton and his other Commanders headed over to Modbury. However, when Hopton arrived, hoping to find a well-armed force of foot-soldiers capable of laying siege to a town such as Plymouth, instead he found an unarmed throng. He sent for some of Grenville’s men to come over from Totnes to protect the Devon men from slaughter and other forces were sent out to give advance warning should Ruthen send out a force from Plymouth.

Despite these scouts, Ruthen, who was a competent General, managed to get within a half a mile of Modbury before anyone noticed. The whole venture turned out to be a disaster for the Royalists, with many of the Devon leaders being taken prisoner and Hopton and Slanning narrowly escaped capture. Bevill’s men now tried to regain the initiative and rescue the Devon leaders, but they had been whisked away to Dartmouth.

It was now decided the only option was to trap Ruthen in Dartmouth and Plymouth by retaining forces at Totnes and placing another force at Plympton. (See two sets of arrows.)

We are now in November 1642. The Devon leaders, despite their set-back at Modbury, wanted the combined forces to lay siege to Exeter. They suggested that help would be at hand near Exeter to ferry their men across the river Exe. Hopton had three options; he could close the year continuing to hold the South Hams and a containing Ruthen or retreat back to Cornwall or to accept the Devonian promises of support and advance on Exeter.

Hopton decided to head out of the South Hams towards Exeter. The Cornish were not keen on this move, having been let down too often, but were encouraged by the promise of extra money and the Cornish army had now become quite a force. However, Exeter was a well defended City and was reputed to have 8000 Roundhead troops to man the defences. The Royalist forces did surround the city, having been ferried across the Exe with a captured ship, but the ship was ultimately lost, and the Cornish realised they had no means of retreat should the need arise.

The siege continued throughout the rest of November and December and Hopton and Ashburnham went to the Mayor of Exeter asking him to surrender the city. But the Mayor was aware that Earl Stamford was on his way to rescue the city and was not prepared capitulate. Worse still for the Royalists was the fact that Ruthen had somehow arrived with his men, slipping through the Royalist lines and were in place not only to defend the city but set about attacking some of the Royalists to the east.

This was not going according to plan; the Cornish men were becoming restless and short of ammunition. Hopton had no option but to call a halt to the siege and retreat back to Cornwall.

The Cornish retreat took them around Crediton and Bow to Okehampton. They were aware that Ruthen had sent a message to Barnstaple men to come to help him cut off the retreating Cornish.

The Cornish, however, had regained their order and were not going to be stopped from getting home. When Ruthen’s force did arrive, they were promptly dispelled by the Cornish and the Cornish managed to cross the Tamar at Launceston and were secure.

Bevill, no doubt realising that the Earl of Stamford was planning to head West, wrote to his wife Grace at Stowe on 6 January 1643. He wrote:

“I am of a mind to billet some companies in the parishes about you as namely five companies in five parishes, by one in a parish for a defence against plunderers. Wherefore, Mr Ross to prepare the inhabitants of Kilkhampton, Morwenstow, Stratton, Poughill and Launcells to diet a hundred men a parish in several houses. They should be allowed for each man two shillings by the week, which is enough from a poor soldier, and to be brief, if they will not do it willing, they will do it whether they will or no. And in this I expect a speedy answer”.

Parliament by now had heard that the King's army was in complete possession of Cornwall, and had occasionally been making incursions into Devonshire, so by 13 January Earl Stamford, Lord General of the parliamentary forces was on his way to Cornwall.

Ruthen had beaten the Cornish back from their ventures into Devon, especially at Modbury and at Exeter and probably thought the Cornish would now be a bit dispirited. So, Ruthen was impatient to attack the Cornish. They bombarded Saltash from ships for about a week and, meanwhile he sent a contingent to cross the Tamar at Newbridge, near Gunnislake, seven miles further north of Saltash.

The Cornish army were in danger of being outflanked so Hopton decided to retreat all forces towards Bodmin and muster once again Moilesborough Down. (Hopton movement in red) Meanwhile, Ruthen crossed from Plymouth to Saltash (in blue), joining up with his Newbridge contingent (in green); the combined forces then marched towards Liskeard.

The Cornish having successfully gathered at Moilesborough and got themselves back into good order, advanced towards Bocconnoc, where they camped the night. They were all agreed that they must defeat Ruthen before Earl Stamford could join him in battle.

The Parliamentary army led by General Ruthen's had been drawn up upon Braddock Down. Battle commenced on the 19th of January 1643 and, once again, the Cornish were successful on Cornish soil and came out as victors. Liskeard was taken the same day and Ruthen fled to Saltash, which he hastily fortified.

The King's forces now dividing, Sir John Berkeley and Colonel Ashburnham, with the volunteer regiments, went to attack the Earl of Stamford, the parliamentary general, at Tavistock; Lord Mohun and Sir Ralph Hopton, with the remainder, proceeded to Saltash and this was quickly taken by assault, Ruthen escaping by water to Plymouth.

Image shows Sealed Knot enactment.

Stamford needed time to reorganise, so he proposed a conference to discuss a possible truce, but this was not agreed. Hopton wanted to keep up the momentum and headed with his forces for Plymouth which was soon surrounded, as was nearby Plympton. Clearly, the Roundhead forces were in trouble, and they arranged for further reinforcements with Sir George Chudleigh and his son James coming to the aid of the Parliamentary forces. This led to a number of skirmishes to relive Plymouth.

James Chudleigh was a formidable leader, and he skilfully fought his way among the various Royalist forces and he knew the area well. This led to a significant further battle as his force moved out of the Totnes area to Modbury (blue) where the Royalist Commander, Berkeley, was forced to retreat back to the Cornish border. He lost a number of men in this encounter.

Hopton now appointed Roborough Common as a rendezvous for all Royalist forces in Devon and from there they moved into Tavistock to take stock. They concluded the safest strategy would be to return to Launceston. In fact, the war for both factions was at a bit of an impasse and a truce of seven days was agreed on 28 February. For the moment, it seemed that Devon and Cornwall might achieve the peace that they sought.

But this was not to be, both counties were fated to become the scene of repeated bloodshed. So this whole period was a difficult period for the Cornish having been chased and outflanked by Chudleigh.

Just before the expiration of the truce, Major General James Chudleigh advanced with a strong party of the parliamentary forces against Launceston, which was then the headquarters of the King's army: this attack had not been anticipated by the Hopton and Chudleigh’s force gained an advantage and nearly defeated the Cornish. However, Sir Bevill and Lord Mohun’s men stood firm in defence of their canon train, and in the end the Cornish got the upper hand and repulsed, Chudleigh’s force and he and his men were obliged to retire into Devon.

It was quite costly in men and equipment. Sixty Cornish killed, twenty taken prisoner, 100 horses taken, and a quantity of muskets and powder was lost.

Following this encounter with Chudleigh, the Cornish became a little disorderly and Hopton was unable to turn the encounter into a total rout. However, the Cornish were tired after long and hard fighting and marching. A day’s rest was necessary.

But, on 25th April 1643, the Cornish set off for Okehampton where they expected to meet with the Devon Royalists. (Red on Map)

On the Wednesday, the Cornish advanced to Bridestowe, six miles from Launceston where they settled for the night before advancing further. Here they met up with the Devon force and were now a sizeable army of 3000 foot and 600 horse and dragoons.

At Bridestowe there was a bit of a skirmish with some of James Chudleigh’s Scouting parties, but the force headed on for Okehampton. Spirits were running high within the Royalist columns, but they had seriously underestimated the courage of Chudleigh and his men. He had set a trap for the advancing army and his men drove through the columns of the Devon and Cornish men, causing disarray. It is possible that the Devon men were less experienced or trained than the Cornish and many of them ran.

Fortunately, Bevill Grenville and Mohun’s men stabilised the situation and prevented a total disaster, but the Cornish had very definitely lost the initiative. More of Chudleigh’s force had now come out of Okehampton to join the battle and the weather was developing into a full storm. Hopton had no option other than to call a retreat and the Cornish slowly made their way back towards the Cornish border and eventually crossed the Tamar back to Launceston. (Green on Map.)

Following this major skirmish Hopton’s force appears to have remained at Launceston while Grenville and his men returned home to Stratton and Stowe. The Earl of Stamford meanwhile met up with Chudleigh and decided to advance on Cornwall with a large army, setting out from Exeter.

He judged that North Devon and, probably some of North Cornwall and, even Stratton was less committed to the King's cause. He also realised that the only weak point to cross the Tamar was somewhere around Bridgerule; from where it was just a short march to Stratton. He sent an advance Guard of horse to find a suitable battle site and they chose the location of an old Iron Age fort on an escarpment just to the west of Stratton. The force entered the county around 11th May 1643, and set up camp on the site now known as Stamford Hill. They had 5,400 soldiers and 13 cannons.

However, 1200 horse, led by Sir George Chudleigh (father of James), were sent to Bodmin to prevent the High Sheriff and his forces from coming to the assistance of the rest of the Cornish army, which he succeeded in doing. (Route taken from Exeter in Blue.)

Hopton, at Launceston, clearly got knowledge of the Earl of Stamford’s arrival at Stratton and decided to head north from the Launceston to confront Stamford before he could recall his Bodmin cavalry force. Hopton was well aware that his forces were diminished due to the success of Chudleigh containing the Sheriff and his trained soldiers at Bodmin.

Hopton and his force left Launceston on Saturday 13 May and headed for North Petherwin, not many miles out of Launceston; here they set up camp upon an open common and ate dried biscuits and little else for sustenance; they slept that night by the hedges. The following day, being a Sunday, prayers were read by the chaplains of each regiment, and they set off again.

The force was aware and, fearful of ambush, by Parliamentary scouting dragoons, and these were encountered enroute. They advanced a further six or seven miles to Week St Mary where again they were harassed by Stamford’s Dragoons.

In fact, the author found some remnants of these skirmishes on his family’s farm near Bakesdown- just to the east of Week St Mary. On Monday 15th May Hopton’s army set off for Bude, eventually arriving on the south downs that evening.

Sir Bevill Grenville’s men were already stationed there and were mighty relieved to see Hopton and his men arrive, as they were very exposed to attack from the Parliamentarians.

It is probably the case that the river Neet estuary and the small “pass” by the tidal mill at Bude, protected Bevill’s men from serious assault.

On arrival, Hopton arranged an urgent Council of War at Ebbingford Manor, Bude. (The Manor shown, would have been smaller than today; the right hand “L-shaped” part, with different windows, was most probably of that period.)

Hopton and his other leaders realised they were a much smaller force but had to take the initiative and attack. This was despite the fact that the Cornish had had little sleep over the last two nights and had fought occasional skirmishes while marching and had little food. However, the plan was to attack the hill the next day in four formations: one from the south and one group from the north, with two separate columns dividing the western approach.

The Cornish Royalist army had about 2,400 soldiers and 500 cavalry, compared with the 5,400 Parliamentary forces. Bevill Grenville and Sir John Berkely had regiments of around 600 men each.

Bevill’s men had benefitted from having some rest while waiting for Hopton’s to arrive with the main forces. It is quite possible, therefore, that it was Bevill’s men who were chosen to make their way across the pass over the river Neet and push the forward Parliamentary forces back towards Stratton. (The painting shows the tidal mill at the river Neet as it would have been at the time of the Civil War encounter.)

They succeeded to some degree and camped the night of the 15th on the Downs, possibly on today’s Golf Course.

Early in the morning Hopton’s men also crossed the pass at the tidal mill and the whole Cornish were in place. They soon discovered that the Parliamentary forces had set up advance groups all along the hedgerows leading to the main encampment. The Cornish were going to have to fight a constant battle of attrition as they made their way towards the main battlefield. But equally, the Roundhead forces, settled behind the hedges, were in danger of being encircled by the Royalist four-pronged attack.

At dawn on 16th May 1643, the two sides began to fire their muskets upon each other while the Cornish Royalist formed into the agreed formations. The plan was that they would form four attack groups, each with eight cannons apiece. The first group, commanded by Lord Mohun and Sir Ralph Hopton with 600 Liskeard men; to their left a second group led by Sir John Berkley and Sir Bevill Grenville and their 600 men; again, to their left a further group of 600 Launceston and Saltash men, led by Sir Nicholas Slanning and Colonel Trevannion and a final group of 600 attacking from the north led by Sir Thomas Bassett and Colonel Godolphin. Mr John Digby with his horse and dragoons, being around 500 men, stood upon a sandy common. They were charged with preventing anything that came their way from the enemy camp, which probably meant they were already in place the night before the battle.

The battle really commenced around five o’clock on the morning. It would now be a constant battle of attrition as the Cornish in their four columns tried to push their way forward. These attacks continued into the afternoon with Cornish soldiers with pikes charging against each band of the opposing force and others fired their muskets. Slowly pushing the Parliamentary forces back towards the hill.

However, they could not be moved from the hilltop. An account of the time says,:

“the fight continued doubtful with many countanances of various events till about three of the afternoon, by which time the ammunition belonging to the Cornish was almost spent”.

The fact that ammunition was running out was concealed from all but the group Commanders and Officers. They resolved to advance with “their full bodies, without making any more shot”, till they reached the top of the hill and be on more even ground against the enemy.

The sight of the Cornish running up the hill, without firing, unsettled the Parliamentary forces and they gave up their positions and fled.

An account again written following the battles says:

“ it fortuned that on that avenue where Sir Bevill advanced in the head of his pike and Sir John Berkley with his musketeers on each side of him, Major General James Chudleigh with a stand of pikes charged Sir Bevill Grenville so smartly that there was some disorder and Sir Bevill was overthrown, but was soon relieved by Sir John Berkley and some of his own officers, he was able to reinforce the charge and there took Major James Chudleigh prisoner”.

Chudleigh was a formidable Commander, and his loss would have been a significant blow to Parliamentary forces. Lord Stanhope had within his command a force of horse but chose not to use them in the battle. However, he did use them to escort his ignominious retreat to Exeter.

The Cornish were in full praise of Major General James Chudleigh, “who had behaved himself with much courage as a man could do”.

In fact, Major General James Chudleigh was so impressed by the Cornish that he later changed sides and joined their force. His father, Sir George Chudleigh, also received praise as he had carried out his role so admirably in containing the Sheriff’s Royalist soldiers at Bodmin.

The photo shows the comparatively level ground to the north, as taken from the focal point of the battle. The scene is little changed from that of the 17th Century.

Of this battle it was written:

“They (the Cornish) divided into four detachments, all of which, with wonderful perseverance, gained the summit of the hill on which their enemies were stationed, and obtained a complete victory. The Earl of Stamford realising the battle was lost, fled to Exeter. Considering the great disadvantages of the ground, and the superiority in numbers of the parliamentary army, which was more than double that of the King's, this has been esteemed by historians as one of the most brilliant victories in the whole course of that unhappy war. A later writer calls it "the single and most astonishing instance of what determined valour can effect."

The consequence of this victory was that the whole of the parliamentary camp, with all the baggage, provisions, ordnance, ammunition, and a great number of prisoners, fell into the hands of the Cornish army. Sir George Chudleigh still doing his duty containing the Sheriff and his forces at Bodmin, heard the news of the Earl of Stamford's defeat, he made a hasty retreat with his horse to Exeter. Parliament lost this battle but were the ultimate winners of the war, and history is always written by the winners. The hill on which the Cornish fought so bravely is named after the Lord Stamford who sat protected by his cavalry so he could make a hasty retreat should the need arise - which it did of course.

Following the Battle of Stamford Hill, the county of Cornwall was now in a state of security, the King's generals left for Saltash and Milbrook, to check any incursions from the parliamentary garrison at Plymouth and from there marched with their main forces to join Prince Maurice, and the Marquis of Hertford, in Somersetshire.

The commemorative tablet shown was placed by the Bude-Stratton & District Old Cornwall Society in 1971.

Following the battle at Stamford Hill Sir Bevill and the rest of the Cornish army headed for Okehampton. From there he wrote a letter to his wife Grace saying he was somewhat bruised from the battle and that he had spitted blood for two days and bled at the nose so much. I had no slat neither, but I do not need it now. (Slat is a drink of ground slate!)

The same day the King wrote to Bevill:

“To our right trusty and well-beloved Sir Bevill Grenville at our army in Cornwall; Charles R.”

“Right trusted and well-beloved wee greet you well. Wee have seen your letter to Endymion Porter our servant. But your whole conduct of our affairs in the West doth speak of your zeal to our service and the public good in so full a measure as wee rest abundantly satisfy’d with testimony thereof. Your labours and your expenses wee are graciously sensible of, and our Royal Care hath been to ease you in all that wee could”.

The lengthy letter ends with the lines: “Wee shall reflect upon your faithful services as you and yours shall have cause to acknowledge our Bounty and Favours. And wee bid you heartily farewell. Given at our Court at Oxford the 24th May 1642/3”.

One wonders what bounty would have been bestowed on Sir Bevill had he survived.

Battle of Lansdowne:

To complete the story of Sir Bevill Grenville during the Civil War period, we must give some account of the Battle of Lansdowne, Bath 5 July 1643, where he lost his life.

There are several accounts of the battle but perhaps an extract from the summary prepared by English Heritage, which is given below, captures the drama and heroism of Sir Bevill and of his Cornish men.

It is typical of Civil Wars that the field Commanders of the two opposing forces at Lansdowne were Sir William Waller, Royalist, and Sir Ralph Hopton, Royalist both of whom were close friends before the war. But they, like everyone else had to take their sides and fight for their cause.

The Heritage England summary follows with the spellings of the day retained:

While the Royalist troops waited for orders in the valley they were subjected to fire from the Parliamentarian guns on Lansdown Hill. Hopton's Cornish infantry, who were men of strong self-belief, rapidly lost their patience and, as Colonel Slingsby records, they pleaded to be allowed to attack Waller's artillery:

Now did our ffootte belieue noe men theire equals, and were soe apt to undertake anything for they desir'd to fall on and cry'd lett us fetch those cannon.

Hopton at last gave way and ordered both Horse and Foot to storm Waller's position. The central attack was to be delivered by the Horse who would advance up the escarpment via Freezinghill Lane, while musketeers attempted to drive the Parliamentarians out of the woods on either side of the road. If successful, the infantry would then outflank Waller's line.

Unfortunately for Hopton, the Royalist Horse were repulsed with lost and it was only through the intervention of Colonel Sir Bevill Grenville that the momentum of the attack was maintained. Seeing the Royalist Horse falling back in confusion Grenville led his Cornish pikeman forward up the Hill with musketeers in support on his left and cavalry on his right.

With their progress partly screened by the wall to the left of the road and by dead ground, the Cornishmen pressed on up the escarpment only to meet a withering fire as they crested the rise. The advance came to a rapid halt and Sir Arthur Heselrige's Regiment of Horse charged the Cornishmen three times as they struggled to establish a position on level ground.

In the third charge Grenville and many of his men were cut down:

Sr Beuill Grenville....gain'd with much gallantry the brow of the hill receiving all their small shott and cannon from theire brest worke, and three charges of horse two of wch he stood, but in the third fell with him many of his men. Grenvile's defence had for the moment broken the offensive spirit of the Parliamentarian Horse at a decisive point in the battle: ....yett had his (Grenvile) appearing upon the ground so disorder'd the Enemy, his owne muskeiteires fyring fast upon theire horse, that they could not stay upon the ground longer; the Rebells ffootte tooke example by theire horse and quitt theire brestworks retyring behind a long stone wall that runs acrosse the downe; our ffoote leps into their brestworks; our horse draws up upon theire ground: our two wings that were sent to fall into the two woodes had done theire businesse and were upon the hill as soone as the rest.

Waller now pulled his troops back behind the shelter of a stone wall some 400 yards behind his breastworks on the edge of the escarpment. The Royalists were thus confronted by a second, not inconsiderable line of defence which would have to be stormed:

The Enemy (obseruing our ffront to enlarge it selfe upon the hill, and our cannon appearing theire likewise) began to suspect himself, and drew his whole strength behind that wall, wch hee lined well with muskeiteires, and in seuerall places broke down breaches very broade that his horse might charge if theire were occasion, wth breaches guarded by his cannon and bodyes of pikes.

It was stalemate, for the exhausted Royalists could not muster the strength to go forward into a second curtain of fire:

Thus stood the two Armys taking breath looking upon each other, our cannon on both sides playing without ceasing till it was darke, legs and arms flying apace, the two Armys being within muskett shott: After it was darke theire was greate silence on both sides, att wch time our right wing of shott got muche nearer theire army lodging themselves amongst the many little pits betwixt the wall and the wood from whence wee gald them cruelly. For many Royalists, such as Richard Atkyns, the lull had barely come in time, for the young Captain found the edge of the plateau to be a most unhealthy deployment: When I came to the top of the hill, I saw Sir Bevill Grinvill's stand of pikes, which certainly preserved our army from a total rout, with the loss of his most precious life:

they stood as upon the eaves of an house for steepness, but as unmovable as a rock; on which side of this stand of pikes our horse were, I could not discover; for the air was so darkened by the smoke of the powder, that for a quarter of an hour together (I dare say) there was no light seen, but what the fire of the volleys of shot gave; and 'twas the greatest storm that ever I saw, in which though I knew not whither to go, nor what to do, my horse had two or three musket bullets in him presently, which made him tremble under me at that rate, and I could hardly with spurs keep him from lying down; but he did me the service to carry me off to a led horse, and then died: by that time I came up to the hill again, the heat of the battle was over, and the sun set, but still pelting at one another half musket shot off..

With the fall of Sir Bevill, it is said that the Cornish spirit collapsed. But it can be said that he achieved his honest name and a honourable grave.

= = = = = = = = = “ = = = = = = = = = = =

The aftermath of this event on Sir Bevill’s family, on his ancestors and, on his faithful servant Anthony Payne, is told in the final part four of the

Grenville family story.

If you enjoy reading about our history without any adverts appearing, please help me to meet all the cost with a small donation.

For extra security, the link below will take you directly to the Paypal payment centre without an intermediate stage.

For more details of how this donation will benefit you and young local people to our area, please select “info” on the menu button.

Your payment will be much appreciated, however small, thank you.