Week St Mary

Like so many of our valley stories, the story for Week St Mary weaves its way through local great families, the Normans and deep history going back to the Romans and beyond. So, this story is broken up in separate subjects with links as appropriate.

The walk up through the woods and valleys are wonderful and unspoilt, but your appreciation for what you see will be greatly heightened by understanding the historical background.

The recorded history for Week St Mary reveals a Saxon in possession of the estate named Cola. He lost his manor to Richard Fitz Turold, with the coming of the Normans. The estate later changed to the Blanchminster family, who held land principally in Stratton at Binhamy or Bien Amie. We also have the folkloric tale of Thomasin Bonaventure or Tomasin- a French name for Good Fortune, which it could be said she had and became a major benefactress to the community as Dame Thomasine Percival.

The story of these individuals is discussed under separate links and headings taken from this website’s menu.

The Domesday Book of 1086 records Week St Mary (Wich) being held by Cola during “The Reign of Edward” (T.R.E.), that’s up to the 5th January, 1066, It was then held by Richard Fitz Turold, son of Turolf from Count Robert Mortain.

The Name of Week derives from the Saxon word “Wich – sometimes spelt Wyke – and this signifies a dwelling or fortified place. Such settlements in Norman times also signify a community linked with salt production and distribution. The word “wich” itself derives from the Latin “vicus” meaning dwelling place, village or hamlet.

Most historical accounts of Week St Mary tend to start from the Domesday Book record of 1086, which is understandable as it is the first time for many villages that we have written records of its inhabitants and its make up. And so, in the Domesday record, we see that the estate at Wich had been held by Cola at the time of King Edward the Confessor before 5th January 1066.

It is interesting to note that the name Cola is typical of a period before modern names came in to being. Initially, people were named according to their work, the nature of their home or even their main colour features; example, Fletcher, Green (a person who lived by the green) or Brown who had brown hair. “Cola” appears to derive from dark charcoal features. It is not inconceivable that the name may also derive from the Latin word “Agri-cola”, someone who is engaged agriculture and the growing of crops. Cola may have taken his name from Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the Roman conqueror and Governor of much of Britain 77/78 to 84AD.

Week St Mary lies in the area of the dotted green line, that is the route towards Boscastle and Tintagel, avoided Bodmin Moor and the numerous boggy and wooded valleys.

However, to return to the name of “Wich” and its meanings. We have said that it can mean a dwelling place. But in Angle-Saxon England it can have a specific meaning of a “wich-town” – a settlement characterised by extensive artisanal activity and trade. This is interesting in the context of Week St Mary as we cannot ignore its location in its geographical landscape. A glance at the image of the topographic landscape will help to highlight this more clearly. It is situated just to the north of Bodmin Moor, yet near to the river Tamar and a comparatively easy crossing point to communities in the east. There were communities at modern-day Whitstone, Bakesdown, Marhamchurch, Jacobstow and Pounstock- all significant places in the distant past.

There are known to be ancient “holloways” (paths sunken by constant use or within weather protecting embankments), nearby packhorse routes leading from the Tamar; the hilly terrain offered obvious opportunities for Iron Age forts – and there is an Iron Age fort at Week St Mary or Wich called Ashbury.

Iron Age Forts are now considered to be places where trade and exchange of animals took place, as well as places for festivities, gatherings and celebrations. Nearby too, at Froxton Farm are numerous earthworks, some of which have Roman (square-form) characteristics. And it is known that there were Roman “milestones” found in the general area indicating that there were Roman roads avoiding the deep valleys and Bodmin Moor enroute to Tintagel, or the Roman signal station at St Gennys and the Roman garrison at Nanstallon, just three kilometres west of Bodmin.

When considering the location of villages in historical time we should not overlook proximity to the sea. This is important for two reasons, firstly, significant trade was conducted by extensive sea routes to the whole Celtic nations and these communities needed to trade widely. Also, the need by all communities for salt.

Week St Mary is not far from Widemouth Bay or in Cornish “Porth-an-Men” the port for stone or rock. Presently being investigated by the author is evidence of possible metal smelting on the shoreline at Widemouth- was this “rock” iron ore brought down from North Devon and Somerset via the Bristol Channel? (See second image of ionised foundations on the shoreline.) At the time of the Doomsday Book there were ten salt houses along the river Neet at what is now Bude and even today, Widemouth Bay has a property called “Salt House”. (Arrowed on Image.)

Week St Mary is just out of this image in the top left-hand corner.

So, Wich historically was an obvious meeting and trading place, and it is not surprising that there were significant farming manors around the area and suggestions of marketplaces or trading assembly areas. Even in the 1841 census the population has a high number of traders and artisans.

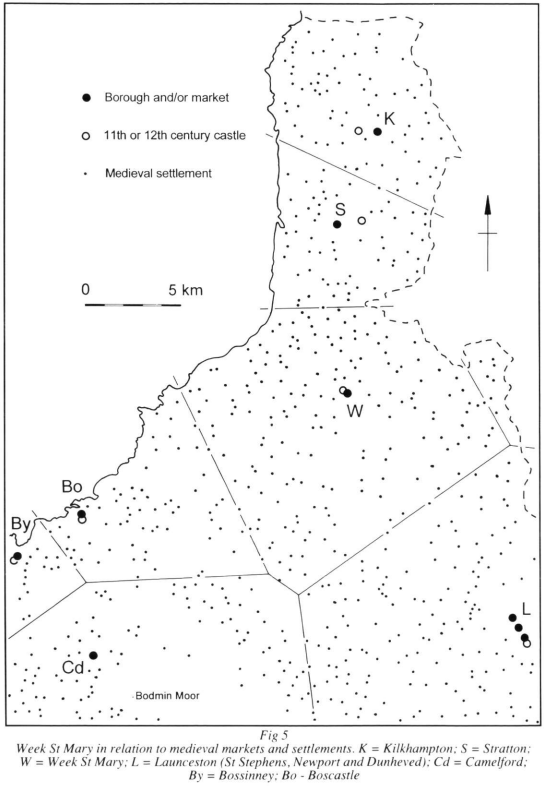

It is no surprise therefore, that the Normans should settle some very important families here and in time build a castle as a statement of new ownership and authority. These Norman settlers eventually, created new markets near their castles and these can be identified at Kilkhampton, Stratton, Week St Mary, Camelford and Launceston. These are all distanced to enable local people to carry their produce or drive their animals to the local market over a convenient distance of half a day’s walk. Archaeologists have taken this to suggested that the Lords of these Castles brought about these markets, which for our modern idea of markets is true. However, it could be argued that the Lords built their castles where there were obvious existing trading routes or focal points.

We may accept that Wich or Week St Mary was one such focal point, but we also have the watershed route of Kilkhampton and Stratton; also, at the Tamar crossing point to Cornwall at Launceston, we have a Norman castle; plus, to the west of Bodmin Moor we have markets at Boscastle and a market town at Camelford. It is more a question of what came first.

Image produced courtesy of Cornish Archaeology, No 31, 1992 :

“Week St Mary: town and castle by Ann Preston-Jones and Peter Rose”

Regarding Iron Age forts; there was one at Stratton, a suggestion of one at Kilkhampton, there is the one we have seen at Week St Mary and a large fort at Warbstow, just to the south of Week St Mary; not to mention a further Iron Age fort at Castle an Dinas, at St Columb Major. During Neolithic and Bronze Age times, Rough Tor itself was a sacred gathering place for a very wide community. In other words, this was a very active area in pre-history and it is wrong just to view our history from what was written in 1086.

The image is again produced courtesy of Cornish Archaeology, No 31, 1992 and shows the corridor of Cornish Rounds (3-4) and the hillfort at Asbury. Cornish Rounds are late Bronze Age and Iron Age small enclosed farmsteads or hamlets.

Although jumping forward in time, there is a further link to trade in the local folklore connected with the story of Thomasine Bonaventure. This involves her meeting with a wealthy trader passing through Wyke or Week St Mary in 1463 and being invited to join his household in London as a maid servant to his then wife. This led to a succession of marriages to wealthy husbands and, at each event, leading to enhancement of her wealth until she was able to her engaged in much local benevolent work which, upon her death in 1530, included a school for the parish of Week St Mary - we will see this school during the walk at “Castleditches”.

So, we now see Wich as a trading centre connecting a wide circuit of communities and part of a major trading route into Cornwall.

(Image courtesy of Cornwall Heritage Trust - links below.)

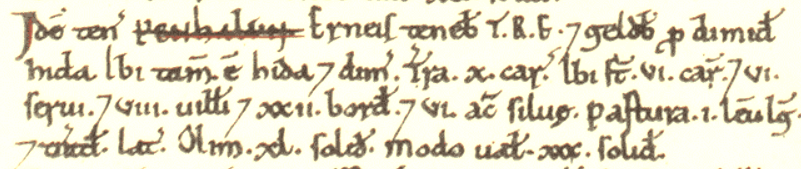

Above is the Domesday Book record for Penhallym (Penhallum) which shows that it was held by Erneis T.R.E and then came into the estates of Richard Fitz Turold from Count Robert Mortain. Clearly, this says that there was a significant property here at the time of King Edward the Confessor.

Prior to 1086 we know that it was the “Cola” who held the lands at Wich at the time of Edward. He is replaced following the Norman conquest by Richard Fitz Turold. (The “Fitz” prefix denotes “the son of” Turold or Turolf.) Turold had been a member of Wiiliam the Conqueror entourage. He had been awarded well for his service and held Cardinham from the Earl of Cornwall; that is King William’s half-brother Count Robert Mortain. This not only included Wich, but also a manor or property at Penhallym.

At his father’s death Richard Fitz Torold inherited his father’s estates, and this led to enlargement of Penhallym, as a summer residence and, no doubt, the development of property around the village of Wich. In 1086 the Domesday Book records that the village included six villagers, and ten smallholders.

Richard Fitz Torold was steward to Earl Robert Mortain and became one of the most powerful men in Cornwall. His descendants would eventually adopt the name of Cardinham as their main seat was at Cardinham Castle.

Subsequently, the manor at Wich was sublet by the Cardinhams to a family who adopted the name “de Wyke”. This family in the twelfth century also held land on the Isles of Scilly. In the second half of the 13th century (c1259 AD), the estate of Wich passed to Ranulph de Albo Monasterio following his marriage to an Isabella (assumed to be a de Wkes.)

It is not known which of the above families decided to build themselves a castle at Wich (Week St Mary) very close to the village centre in the 11th or 12th century; there is nothing to suggest it had a real defensive purpose and a castle is not mentioned in medieval records. This may have elevated Week St Mary to Borough status.

The Albo Monesterios eventually changed to their name to Blanchminster. The Blanchminster principal seat was at Stratton and in 1335 a Ranulph de Blanchminster sought permission from the King to crenelate his moated manor at Binhamy, Stratton.

Image produced courtesy of Cornish Archaeology, No 31, 1992 :

“Week St Mary: town and castle by Ann Preston-Jones and Peter Rose”

The full story of these families is told separately, but we now have an image of early life around Week St Mary. A village with an active market of traders, farmers and artisans, with regular markets taking place within the market square – in fact a triangle. Alongside the church is “Castleditches” (or Castle Hill) most probably the site of the medieval castle, but now some of the local inhabitants are wealthy enough – the burgess – to have burgess plots radiating out from their main street homes. That is the narrow strip fields in the image which are so typical of those found in this area.

Nearby are the ruins of the ancient Iron Age fort of Ashbury and, lower down the valley to the west are the remains of what had become a grand summer moated residence at Penhallam (Penhallym in Domesday records.)

From the menu you can now select the walk to Penhallam. A second walk takes you through a beautiful set of woods up to the Iron Age fort at Ashbury and a third walk will take you around the “Castleditches” area and market triangle.

Below are links to the story of the Fitz Turolds and the Blanchminsters, or you may select these links from the menu later.

Also, below a link to the definitive story of Week St Mary Village and a link to Cornwall Heritage site and an account of Thamasine Bonaventure.

https://www.weekstmaryvillage.co.uk/

https://www.cornwallheritagetrust.org/learn/resources/stories-and-rhymes/thomasine-bonaventure

This is a book written by a local person of the village that would be an excellent pre-read before visiting. Available from the village site, link above.