The Bronze Age

This summary is not intended to be a history of the Bronze Age, but it is hoped it will enable a better understanding of this period and provides an historical narrative for what may be discovered in our immediate area. The author is, of course, indebted to the detailed work of many professional archaeologists, particularly those of the Cornish Archaeology Unit (CAU). However, ultimately, the actual content is the interpretation of the author.

It is a complex period of our history that set the way of life for much of what followed later in the Iron Age and Medieval Period. It is a sad fact that many of us are aware of the Roman and Norman periods but know so little of the vast period of pre-history that preceded these events. As a consequence, the physical features left by these people are somewhat ignored. We are in fact, particularly blessed with an amazing heritage along our coast and highways, and particularly so on nearby Bodmin Moor.

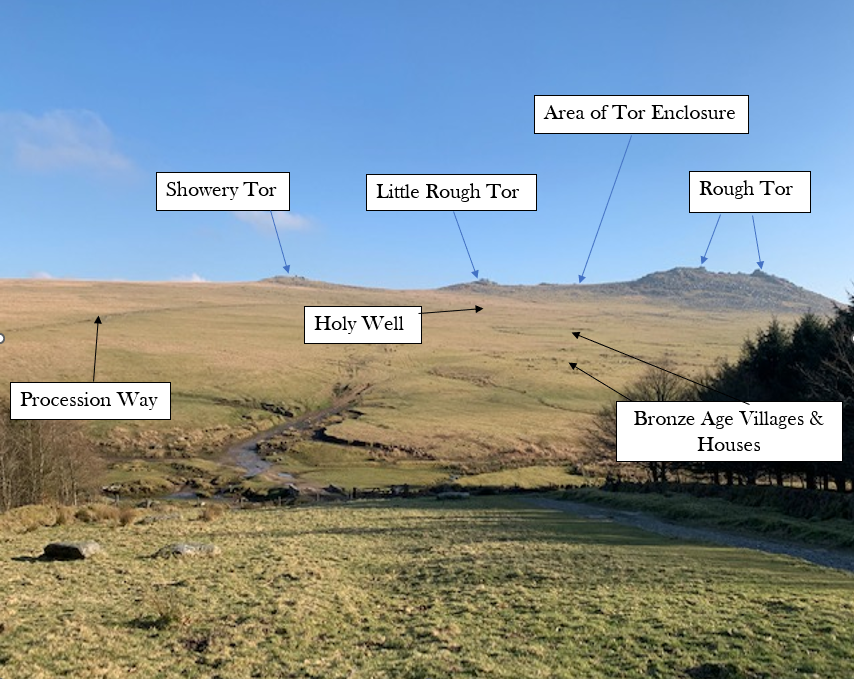

The scene opposite is what presents you as you park your car at the main car park for this area.

This article will explore this period and discuss elements in small steps:

The Bronze Age:

This, of course, is the period when bronze, an alloy of approximately 90% copper and 10% tin, came into use in Europe and represented a major advancement away from the earlier stone implements that had been used since the beginning of man. However, archaeologists also now use a term representing what may be regarded as an early age of the use of metals, namely copper. This is called the Chalcolithic period, most probably introduced to Britain by the Beaker people. More of whom later.

The picture shows a selection of early Irish copper axes found at Cappeen, County Cork. These were the earlies metal axes to be made and were circulated widely in Ireland and Britain.

Cultural Periods

Beaker Using Period. 2400-1700 BCE

Early Bronze Age (EBA) 2050-1500 BCE

Middle Bronze Age (MBA) 1500-1100 BCE

Late Bronze Age (LBA) 1100-700BCE

Cultural Periods:

An archaeologist from the CAU, using advanced metallurgical analysis, has identified four cultural periods for the Bronze Age that will be used in this summary. These are shown opposite.

Note: The Bronze Age started earlier further east in Europe and knowledge of the uses of tin and copper, and skills necessary to produce the alloy passed slowly towards Britain. (The earliest evidence for the use of copper is to be found in Serbia, around 5,500BC and the earliest reference to copper working more locally is at Ross Island in Lough Leane, Ireland 2400BC).

Once the skills were attained communities quickly adopted the technology, but that is not to say that the uses of stone and flint implements stopped being used for certain uses.

Dozmary Pool on Bodmin Moor; Was the throwing of King Arthur’s sword a throw-back to these earlier votive offerings?

Cornwall In the Bronze Age:

Cornwall is rich in Tin and Copper and the early users of these metals will have searched Europe for sources of this valuable commodity. It is possible that the Beaker people who, it is believed to have come from the Rhine area of northern Europe, arrived in southeastern Britain and slowly dispersed throughout the land. It is these well-travelled people who are thought to have introduced copper and later bronze to our shores.

During these early periods of our history, the western Atlantic facing countries, to north and south of our region, were linked by seaborne trade routes. So, Cornwall played a major role during this period being rich in tin, copper and gold. And, being very much central to the western Atlantic trade routes, it is no surprise that these valuable commodities would in time make their way throughout Britain and Europe.

Production of copper was prodigious in such places as the Great Orme in North Wales and Mount Gabriel in south-west Ireland. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the most significant period of production was during the four centuries between 1900 and 1500 BC.

The odd thing is that not all the artefacts that were produced were actually used. Some particularly fine pieces were given as gestures of friendship to tribal leaders, but some were partially melted down and thrown into lakes, while still very hot, as a sizzling, steaming, offering to the mysterious providers of the underworld. (See the Over and Underworld)

North Cornwall and North Devon during the Bronze Age:

Our region will have been attractive to the people of this period. The western flanks of Bodmin Moor had long been an important sacred area, an area for major communal gathering, for summer grazing of animals and the wider Moor area would now be a source for tin, copper and gold.

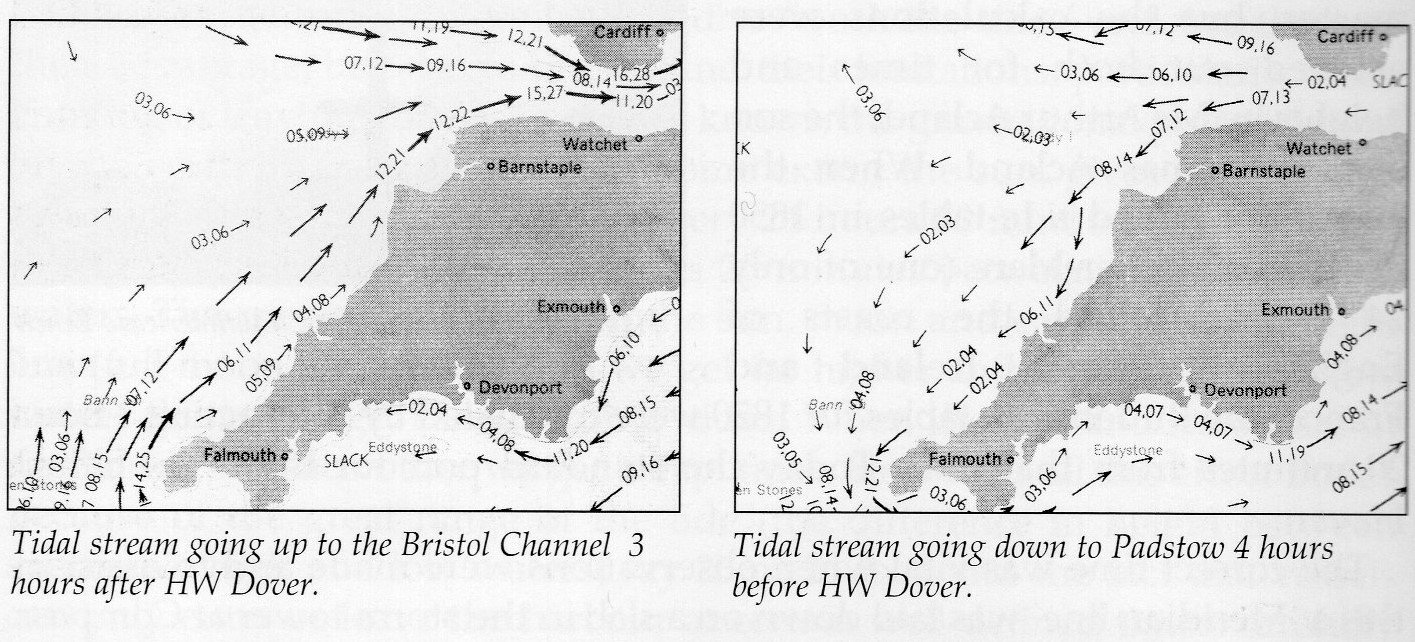

The natural harbour at Bude will have been important to maritime traders. Trade between Wales, Ireland and Scotland was significant and vessels sailing from these regions would call at our harbour for provisions or safety. Of course, some trade may well have crossed the Bristol Channel from Wales and then along our watershed high ground down through North Devon and North Cornwall.

Some produce undoubtedly moved eastward by land, and the river Tamar provided an easy route to the Channel -avoiding the obstacle of Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor – from where small vessels carried produce to other parts of Britain.

The huge Bude Bay

Bude, with its sandy and rocky beaches will have been important for early settlement, having the benefit of low altitude, but also the source of shell food and fish. Of course, the inland areas were used for cultivation and the wooded areas would be important for hunting and, no doubt, good for pig rearing.

Tidal currents that flow northward and then southward with the filling and emptying of the Bristol Channel will have helped mariners make their way to all the destination of the Atlantic seaboard.

With maritime traders visiting our area, local produce will have been exchanged for other commodities.

Climate:

Where these early people chose to settle and grow their produce very much depended on the weather. And fluctuations in climactic conditions are well documented. These changes can be due to the position of our hemisphere in relation to the sun; to sunspot activity on the sun itself; to the vagaries of volcanic activity; to wobbles in the rotation of the earth about its axis, on a grander scale, the distance our planet is from the sun itself. The earth circles the sun on an elliptic orbit and the sun is weakest when the earth is at its most distant point. If any these negative factors coincided, then the consequences will affect climactic conditions, or even bring about an ice age.

To understand this a little more clearly refer to the images;

Every 100,000 years, Earth’s orbit stretches from nearly circular to slightly elliptic and back. Every 400,000 years, this change in eccentricity is even more pronounced.

Every 41,000 years. Earth’s axis tilts around 2.0 degrees more towards the sun; the obliquity then cycles an extra 2.0 degrees away from the sun.

The final sun to earth relation is what is termed “wobble”. Every 26,000 years, Earth completes a wobble on its axis; this is known more technically as precession.

As the climate affected the actions of the Bronze Age people each period will include a brief summary of the understood climactic conditions at that time.

Before we look at the each of the Bronze Age cultures and where and how they chose to settle, we will explore some of the spiritual thinking of these early peoples.

The Over and Underworld

It is always difficult to place the modern mind back to an age when the people, living out their lives, understood so little about the world in which they lived. There were so many mysteries. They had not developed a true sense of past, present and future. Where did they their body spirit come from? Where did their spirits go after death? Were there unknown forces in the soil affecting whether crops grew or failed?

They took from the earth its bounty of tin, copper and gold and the soil with the help of the gods, or supernatural powers that resided there, created the wonders of transforming the seeds into food for their animals and people. The people naturally saw the need to repay these gods, or supernatural powers, rewarding them, or returning to them, valuable items as votive offerings.

Some archaeologists now suggested that the woods, where these people acted out their lives, represented the land of the living; and the land of the rocks were the lands of their ancestors. An example of this is suggested by the Neolithic procession way from the wooded valley on the west slopes of Rough Tor, Bodmin Moor, towards the Tor itself. (See image opposite.)

It is also highly probable that many of stone circles and stone alignments formed part of a ritual procession from the land of the living towards the sacred land of the ancestors. The stone circles do seem to have been arranged to make alignments with each other and with the hills themselves.

There are other cultures in pre-history who it is known believed in the underworld. The “First Nation Americans”, or Ancestral Puebloans, believed they issued from mother earth itself. At the centre of their Kivas was a hole or indentation, called a sipapu, which symbolizes the portal through which their ancestors first emerged into the world of the living. The author found and photographed the image opposite in the desert of Arizona, which graphically illustrates this thinking.

These same Native Americans spent days confined in their Kivas working themselves into a trance to communicate with their ancestors, seeking help and guidance. Individuals would emerge from their Kivas dressed as a Kachina spirit, that would support the growth of a particular arable crop. Such were the concerns of those who were becoming ever more reliant on producing the bounty of the earth for their survival.

In the pages below we turn to the major cultural periods identified earlier.

The Beaker Using Culture (c. 2400 - 1700 BCE)

Climate Note: This is a period of relative stability in the climate, possibly with a slight increase in wetness.

The term Beaker or Bell Beaker culture relates to a people who came to Britain from mainland Rhine area of northern Europe. Their name derives from the bell-shaped drinking vessels found amongst their burials.

It has to be said that there is not a lot to be seen in our region that relates to these people. But there is no question that they influenced life here, and maybe even becoming the predominate culture of Britain. There is some discussion about the chronology and origins of all the artifacts associated with these people, but it would probably be correct to say they were an eclectic, flamboyant, people who influenced the way of life wherever they settled.

There are parallels with the American G.I.s’ of the second world who came to our shores dressed in much more tailored uniforms, a different lifestyle and with a wealth of goods to offer. And so, it was with the Beaker people. They are thought to have lighter skin and modern DNA profiles record significant increases in eye pigmentation markers – they may also have had lighter coloured hair. They celebrated within their groups drinking mead or cereal produced alcohol from their decorated beakers; their leaders may well have sat astride a horse, around his waist a belt with daggers, and over his shoulder a bow and a quiver of arrows. His clothes were of wool which could be dyed in different colours.

They also introduce burial rituals of single inhumation. At first, they may only have carried flint daggers but in time, their contacts throughout Europe introduced the skills of copper craft and later the alloying of tin and bronze. Modern DNA analysis shows their genes very quickly became the dominate type throughout Britain.

As said above, the Beaker people first came into eastern Britain and dispersed northward and then west into Cornwall where their arrival coincided with increased monument building. But, whereas in eastern Britain the Beaker people practiced single inhumations, in Cornwall burials involved cremation. Their influence in Cornwall appears to be mainly in coastal areas and particularly west of the County. But it is clear from the DNA record that these people certainly came to our region bringing new ideas and, really a new way of life.

Settlement and ceremony: Cornwall archaeological investigations at Stannon Down, St Breward, Cornwall

Early Bronze Age (c.2050 – 1500 BCE)

Climate Note: Little change in the climate from from the Beaker period but with a slight decrease in wetness.

The early Bronze Age people continued or developed many of the lifestyles of the late Neolithic. That is the progressive development of arable and pastoral farming, with the higher Moorland sites continuing to be used primarily for summer grazing with temporary structure servings as homes. Most settlements were probably confined to coastal areas but evidence for these has been lost to modern development, farming, or coastal erosion.

The main focus appears to have been in monument construction and the building of stone circles, stone rows and cairns, plus thousands of burial mounds. The latter to be found all along our coastline and stone cairns and much more on Moorland sites. Stannon Down for example, just southwest of Rough Tor, had a ceremonial complex, which was in use from c 2400 -1120 BCE. There is some evidence to suggest that the ritual may have involved moving from wooded areas, representing the land of living, through to stone features representing their ancestors. One can imagine the ceremony on Stannon Down with individual family or tribal groupings passing through their ancestral memorials and then collectively processing towards the sacred Rough Tor, with further ritual and celebration, as the community gathered and feasted.

Showery Tor looking North with the vestiges of the huge cairn lain all around. This view demonstrates how powerful this man-enhanced feature would be in the minds of all who came here.

This was an important time for our local area having sacred ceremonial areas of great significance to a wider community. And, analysis of Cornish metal artifacts, associated with this period, that’s been discovered in Britain, Ireland, Europe and even as far as the Eastern Mediterranean, all demonstrate the importance trade, particularly of Cornish copper, tin and gold. It also examples the degree of trade along the Atlantic trade routes.

We can now see why Rough Tor would take on even greater importance for ceremonial ritual, feasting, inter-community trade and cultural interaction. The importance of the venue and the occasion reinforced by ritual, stone circles and other alignments. And even the grandeur of Rough Tor itself was enhanced; the natural rock outcrop called Showery Tor and the central rock outcrop of Little Rough Tor were both surrounded with massive cairns. Vestiges of which, see opposite

During the feastings there would be an exchange of valuable, or of beautifully made artefacts, between community leaders solidifying friendships. Such exchanges were important in an age when there was no written word, or maybe even words, to express the value of friendship. Cornish pottery reflects the value of these feastings and interactions as Cornish pottery styles were widely distributed for almost a millennium.

Middle Bronze Age (c. 1500 – 1100 BCE.)

Climate Note: As the EBA concluded a 200-300 year wetter spell followed. From around 1200 BC there is a dry and warm phase.

In terms of evidence of settlement, this is the most important period for our region. The area around Rough Tor, Garrow Tor and the nearby moorland at Stannon Down has literally hundreds of stone round houses and field systems relating to this period. In fact, CAU archaeologists have established that these three Tors, which combined represent less than 10% of the moor, has more than one-third of the total number of huts.

Agriculture was going through something of a revolution. The emphasis was clearly on settlement and expansion and ceremonial sites appear to have been abandoned; ritual and burial took place nearer to the settlements.

This four-hundred-year period saw much change in Bronze Age life. Initially, the climate continued to warm, and this encouraged a movement to create settlements at higher elevations. The field systems initially forming small curvilinear shapes with progressively more fields being added over time to produce a small complex of fields. This opened up our moorland to arable farming in addition to the long-established summer pasturing on the higher moors.

On the stony moorland, large numbers of houses were constructed with stone walls, and the field boundaries were of stones removed during soil clearances. It is possible that even at this local level there were climatic consideration. The settlements on the southside of the hills being used for arable crops and the north-western slopes for pastoral activity. See the image opposite - north to top of page.

Lowland area settlements were fewer in number and round houses here had sunken-floors, presumably giving greater warmth and taking advantage of the greater soil depth.

The image shows the complex settlements around Rough Tor. Note the field systems to the south of the Tor with a large straight reave on the western edge. On the north western slopes there are less fields but more round enclosures. There had been some shelter here from the Neolithic and the in the EBA and MBA. However, the settlement pattern here as seen in modern day may reflect the Late Bronze Age (LBA).

A pottery styled called Trevisker Ware – named from the locality where it was first found –became the only pottery to be found in Cornwall and, as an example of the trade taking place, this style spread to Devon, Dorset and south Wales. And some has been found in Kent, Ireland and even in France.

We cannot be exact as to the nature of life here, as different regions responded to the challenges presented by micro-climates and soils. However, we can say that the Bronze Age people became very organised and approached the upland farming with real drive. They almost certainly carried out more woodland clearance and more round houses were built in the shelter of the new field hedges. All this endeavour involved a community effort which will have given the people a great sense common purpose and accomplishment.

The picture shows one of many very small round house, typical of those on the lower western slopes of Rough Tor. The large doorway standing stones face approximately southwest and in the valley is a source of fresh running water. These, however, may be LBA houses.

Community organisation became more sophisticated as populations grew and farming practices evolved. Large blocks of land were apportioned to groups according to an agreed plan. Areas allotted would include a mix of soils, environments and elevations, all with access to a water supply. Each block of land was delineated by a major dividing wall, which on Dartmoor are called reaves. In some cases, the reave would also provide a fenced area which served as animal drove roads to higher summer pastures- keeping the animals away from homes and arable produce.

The huge wall in this picture runs north to south along the western slopes of Rough Tor. To the right were probably the houses of those who attended the animals; the path to the left, or drove road, was the route to higher summer pastures.

However, around the end of the Middle Bronze Age there was a sudden negative climate change. This was very probably caused by a major eruption of Mount Hekla on Iceland. The peat records, dendrochronology and even stalactite growth patterns in Southerland, Scotland all support this. (See tree section opposite showing many years and very narrow rings following 1160 BC.) From Britain Begins, Barry Cunliffe.

There may have been additional factors at play, but Mount Hekla erupting seems the most likely explanation. This explosion was a major event that threw great quantities of volcanic ash into the atmosphere and affected the climate for around eighteen years. It is even possible that it may have caused instability in Egypt and other eastern European regions leading to the ultimate collapse of the Bronze Age in those communities.

Image opposite is of an Hekla Explosion collected by the author in Iceland in 1977.

On the higher moorland elevations, arable crops and corn harvest were less successful and there was a progressive movement of people to lower ground and coastal areas. It is also possible that population growth and overuse of thin soils may have contributed to less successful harvests, as would leaching of the soil with increased rainfall. Certainly, on the moorland, pastoral farming became the main activity - as may have been at all higher elevations settlements.

There is now evidence of adjusting to these new challenges. Earlier curvilinear fields on the slopes of the Tors are cut across by long rectilinear field boundaries, more suitable to stock control. Maybe this was this time that community housing developed into larger enclosures of several houses with smaller animals held within these compounds. It is these clusters of houses within an enclosed area that can be seen today on the slopes of Rough Tor.

This style of nucleated communal living, groups of houses within an enclosed walled area, set a pattern that would evolve into what is termed “round enclosures”. These will become a feature of the final Bronze Age period.

The picture opposite shows just one round house of many sitting within a large stone wall enclosure on the lower slopes of western Rough Tor.

Photo from English Heritage Series 3-2014 Warbstow Bury; Cornwall Archaeology Survey Report by Zoe Edwards.

The Late Bronze Age (c1100 – 700BCE)

The climate, during this phase of the Bronze Age, started to deteriorate and population numbers on the Moors declined. In fact, settlements at higher elevations were largely abandoned and people moved to lower lands and their homes took the form of “rounds”. Ultimately, round enclosure in one form or another would dominate the landscape. The rounds may have been formed by a ditch and bank and a few in Cornwall may have had the addition of palisades. This may simply reflect the availability of wood, depending on the location.

This was largely to keep animals within the enclosure secure and, safe from other wild animals. The building of such structures may also have been a statement to say, “this is our land”. There was after all movement of people, or even communities at this time, seeking their own area in which to settle.

There now appears to follow a period of cultural evolution in that individual groups or families performed specific functions. Again, in part, due to location. Each community round may be involved in rearing animals, other groups arable. Within communities will be specialist such as metalworkers.

Rough Tor will have grown in significance as a gathering area for special feasting, while on the lower slopes a few houses remained for the people who attended the summer pasturing. However, many more ditch and bank enclosure on hill tops are now being constructed. This may have involved large communal involvement, and maybe specialists gangs. These hill top location were in places to be seen by all.

It is quite possible that the local Iron Age fort at Warbstow Bury (image opposite) and the large fort at Castle-an-Dinas, may well have been a locations for these early Bronze Age hilltop enclosures. Both of which will have been visible over extensive areas. They were not built for settlement, but seemingly specifically for special occasions to do with animal husbandry.

A fairly complex life pattern is clearly evolving which must have required some agreed trading arrangement. There would need to be, for example, an exchange agreement between the parties producing different products or having particular skills. Possibly even implying a high level of managed oversight or even a dominate elite class.

This could produce interesting group dynamics, if there were surpluses or shortages, or if one group had a bad year while others were successful.

The Late Bronze Age would not be unique in facing this problem. The Native Americans living in the desert regions of Arizona and New Mexico faced precisely that problem due to the localised nature of rain storms in the desert; some farmers would have rain, and a good crop, other may have a drought that year and a poor harvest. The Anasazi tribe resolved this by constructing large storage areas, with a complex arrangement for sharing food and communal work. (See the Anasazi example on the last page.)

With this new emphasis on hill top enclosures, the earlier Neolithic enclosure on Rough Tor, at this time, is reinforced and the surrounding walls enlarged. (see opposite large area of stone clitter; the remains of the reinforced earlier enclosure.)

It does look as if the building of hill top enclosures involved a significant amount of work and for temporary use on special occasions. This does suggest that they were as much a statement of ownership and community progress as they were of function. This may have given reassurance to a community at times of stress and may also have introduced a elite or warrior class giving a sense of security to the communities. There is evidence of an elite warrior class developing at this time and swords and other weapons appear in the burial records.

These early hill top enclosures and their uses may well have set the pattern for the Iron Age Forts that will be a major feature of the next major period.

Native American Societies and Food Storage at difficult times.

As a little footnote to our Bronze Age story; the Anasazi Native Americans developed a system of co-operative farming in Arizona and New Mexico. Arable produce was stored in great centres such as Chaco Canyon (opposite) and shared among the people. Excess food was traded for other commodities with other local tribal groups and with the tribes of south American. This was during the first millennium AD.

Farmers who had experienced a poor harvest were engaged in work of a community benefit, such as building paths used by inter-group traders.

Ironically, it was an El Nino influenced long period with no rain that brought an end to its success. But once again, there is physical evidence in bone analysis that suggests that those responsible for the storage of crops were something of an elite and were the last to suffer.

There followed a total collapse of the Anasazi society; there name is a Navaho one for the “disappeared ones”.

If you enjoy reading about our history without any adverts appearing, please help me to meet all the cost with a small donation.

For extra security, the link below will take you directly to the Paypal payment centre without an intermediate stage.

For more details of how this donation will benefit you and young local people to our area, please select “info” on the menu button.

Your payment will be much appreciated, however small, thank you.