Kilkhampton

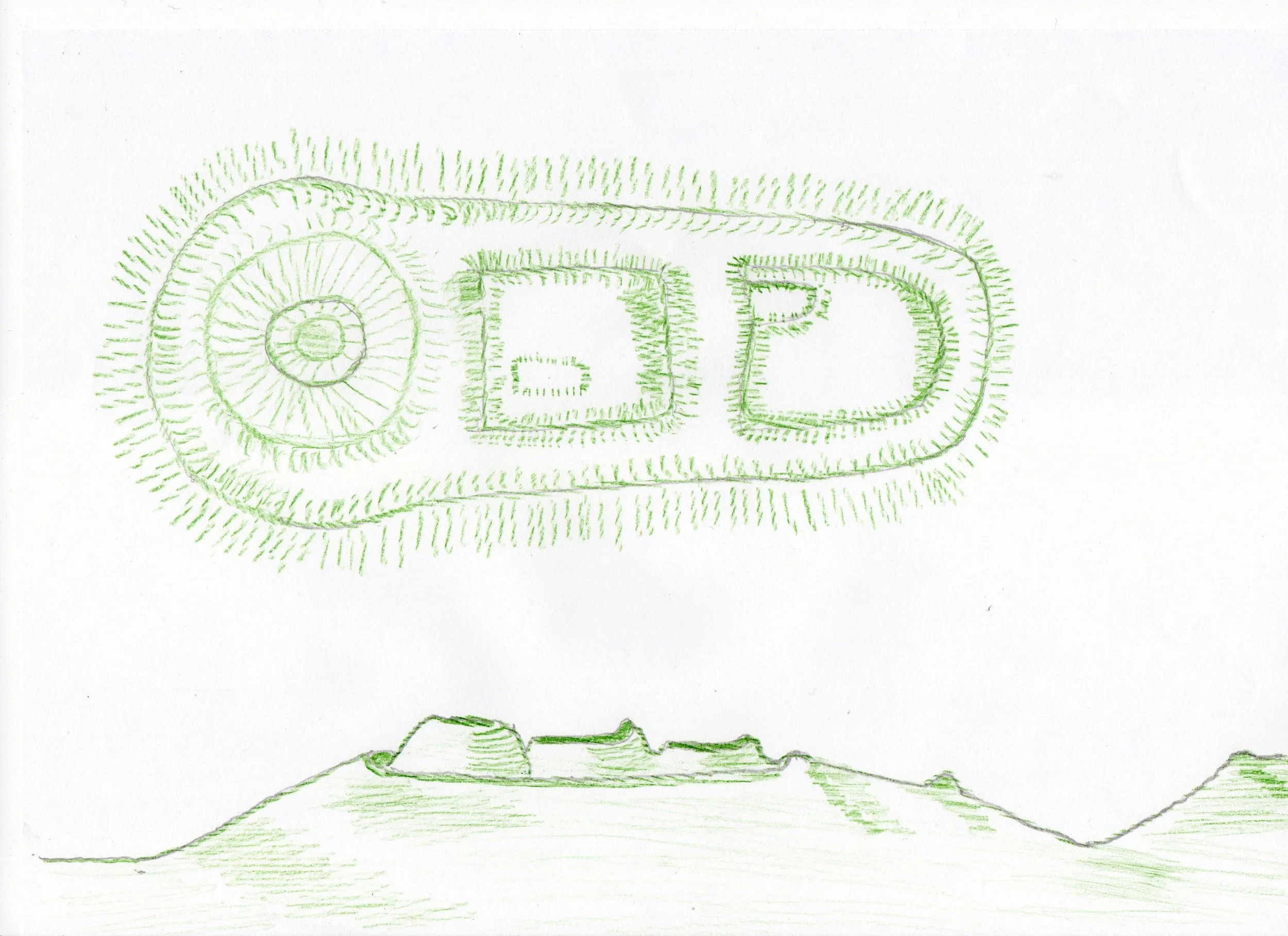

Kilkhampton is a large village with so much history, much of which is viewed through tantalising snippets of information, not least of which is its name. It is thought to have roots in the Celtic language. One suggestion is the Cornish (kylk or kilgh) Welsh (cylch) and Breton (kelc’h) which can be interpreted as “circle or ring”. Archaeologists have suggested that this may refer to a lost circular feature. Such a feature, if one existed, could refer to a defended settlement where the remains of the Norman castle are to be found today. This most certainly would agree with other such enclosure placements, built in Iron Age times. However, there are some who doubt this interpretation; more recent studies suggest an alternative explanation for this name. The Welsh word “cylch” has derivative “cychwy” which can imply boundary; in Gaelic, the word “crich” has the same meaning. The question is, could this name signify a historical boundary pre-dating Athelstan? So even its name sparks intrigue!

If we assume for a moment that buried under the remains of the Norman castle is evidence of this mysterious circle, even the castle has its own intrigue. When the Normans arrived the subsequent Domesday Book of 1086 records Kilkhampton at Chilchetone. The estate of Chilchetone just fifty years later was held by the Robert of Gloucester, half-brother to Matilda the rightful daughter of Henry 1st. Following the death of Henry in 1135, Matilda should have ascended the throne of England. However, Henry had chosen his nephew Stephen of Blois and this led to Civil war. Robert of Gloucester chose to defend his half-sister’s claim, and he may have built the castle at this time. There were many castles built in this part of Cornwall fed by the lure of Tintagel and the legend of Arthur. The Gloucester’s also had a close connection with the Grenvilles and they held large estates at Bideford. They too, may have built the castle at the behest of the Gloucesters which may have been the start of the close association that the Grenville family had with the village.

The image shows the area of the second bailey as seen from the Motte.

Whoever the builders were, it was unusual in design in that it had one motte and two baileys; although an unusual design, a second such castle was built at nearby Stratton. The latter may not have been finished, but both may have been built during the Anarchy period of 1138-53. Both were destroyed following the resolution of the civil war to avoid subsequent bolt holes for unhappy Earls and Dukes, should other disputes arise.

This is a sketch of the castle profile by the host, but based on an original as seen and drawn by the historian Charles Henderson in the early twentieth century.

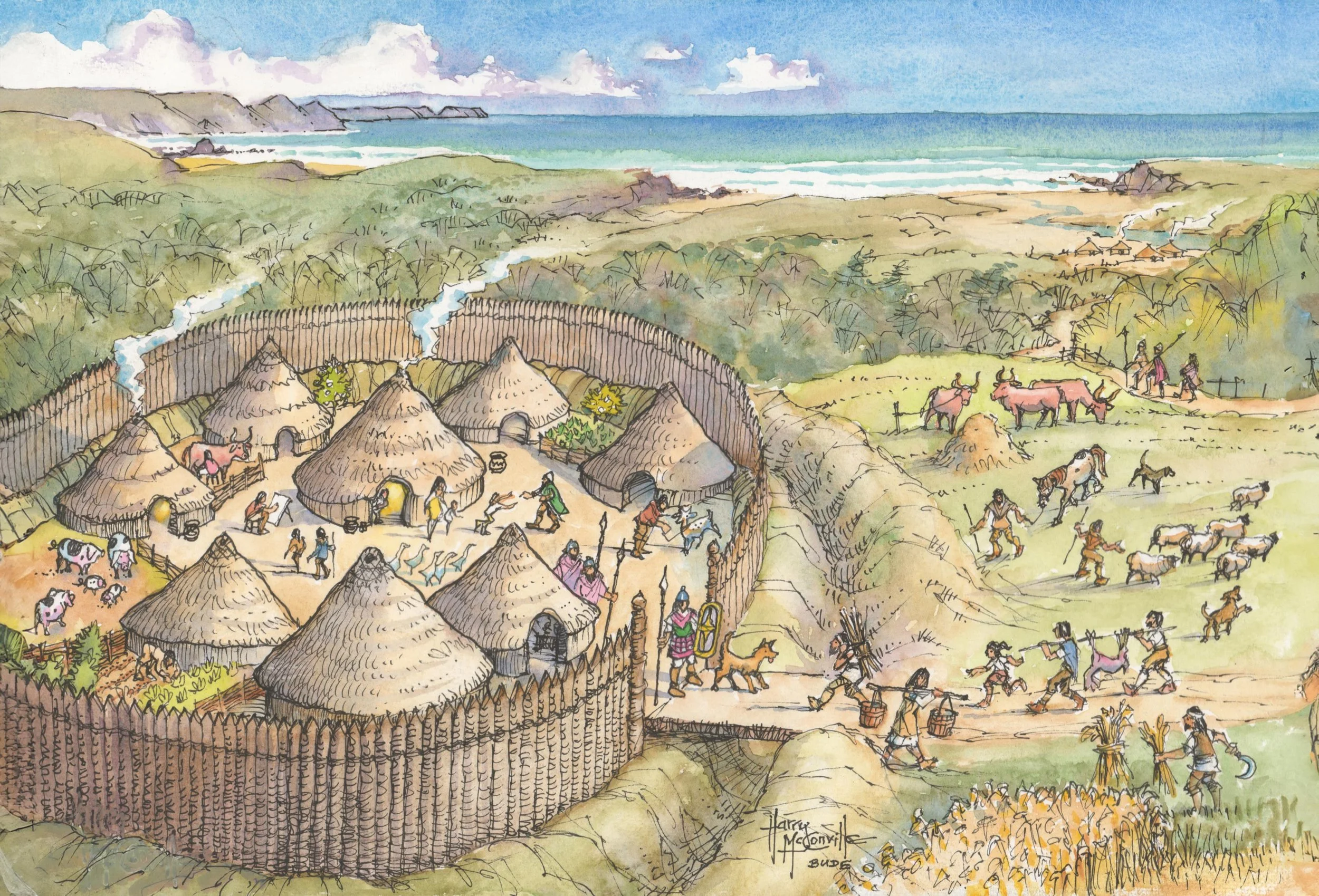

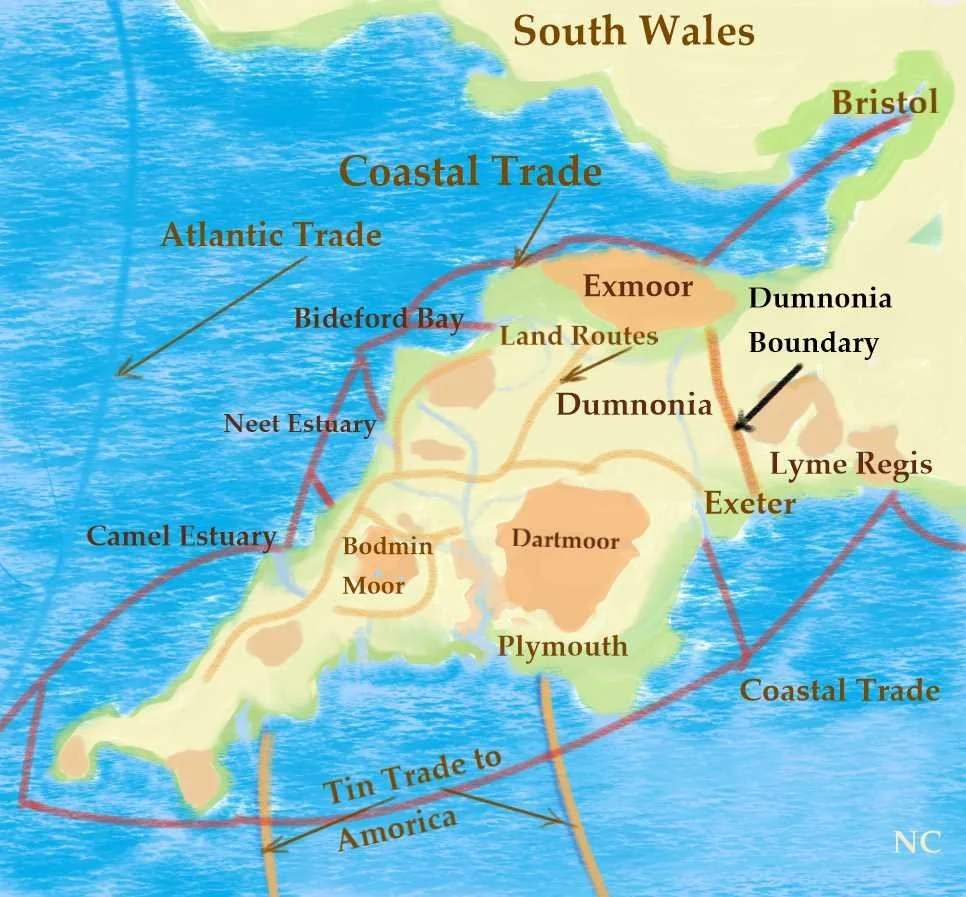

But the Norman period is jumping too far into comparative recorded history. Whatever question marks surround the village name and mysterious circle, this settlement would have been an important location in pre-history, settled as it is strategically placed on the watershed land highway north to south into Cornwall; also placed at the headwaters of the river Tamar, which separates Cornwall from Devon and the rest of England. Also, the village is at the head of the great Stowe valley which leads to the small hamlet of Coombe and on down to the sea at Duckpool, where there was a small harbour connecting the valley settlements to the Atlantic trading highway.

The image shows the view from the castle motte down the Coombe Valle towards the sea. On the sidewalls of the coombe on the left are the remains of Cornish round settlements.

To the north of the village is a Neolithic long-barrow at Woolley – itself rare in Cornwall. This may have been built by the Beaker people who probably moved into the area as they travelled up the Tamar from eastern areas while searching for tin and gold. The modern highway of the A39 follows this watershed which is strewn with Bronze Age burials. The road itself ultimately lead to the large Iron Age fort of Clovelly Dykes, which appears to have been an important trading post, with a possible Roman temple, following initial Iron Age unrest.

The photo shows a section of the enormous long barrow at Woolley. It is not possible to do justice to its size from a ground level image.

At the seaward end of the valley, at Duckpool, in Romano-British times, there was a little piece of industry in the form of a metal processing facility. This probably serviced the needs of the valley community and that of Kilgh – if that is what it was then called.

This the view down towards Duckpool from the little hamlet of Coombe, which not only shows the scene but demonstrates the specialness of the unspoilt nature of our coastline and particularly around this area.

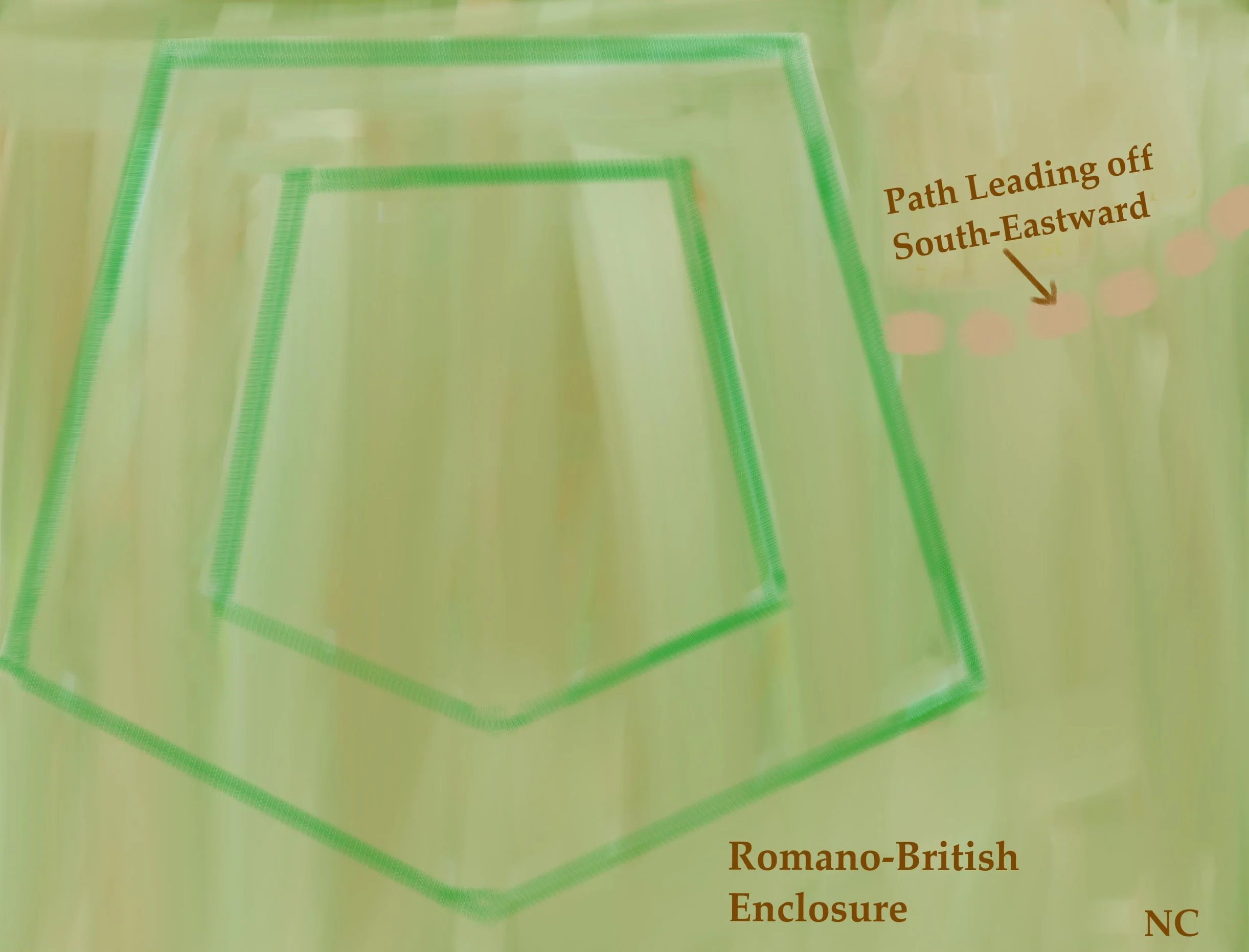

Also, within the land-spurs, which overlook the valley, are the remains of small Iron Age or Romano-British defended enclosures, also known as Cornish rounds.

To find this special place pull down the walks menu and select the Stowe Woods walk. Coombe hamlet is a just a few miles from Kilkhampton via Stibb.

Roman settlements at or near the village is sketchy. Remember, to the north of Kilkhampton, is Clovelly Dykes the Iron Age fort in which there is a probable Roman Temple; very near to Stratton is a structure visible only as crop marking which is suspiciously like a Roman signal station or Romano-British temple. At Duckpool, as already mentioned was the Romano-British metal working facility and very close to the village is a square land feature which suggest possible Roman influence. It is also possible that on the cliffs to the west of Kilkhampton, was a further signal station which gave the Romans some control over marine traffic leading towards the Bristol Channel and South Wales and beyond.

The image shows the crop marking outline of the suspected Roman signal station or Temple near Stratton.

In fact, it is thought there was a network of signal stations on this coast which were linked to inland stations. The painting shows the view from an Iron Age fort on the eastern valley side of the A39, which you pass on the A39 from Stratton towards Kilkhampton. There are three Iron Age forts just on this section of road and the one shown had a view down the coast to a signal station at St Gennys. So, we can be fairly sure that the Romans had quite an interest in the settlement of Kilgh and they may have set up powerful leaders in these Iron Age enclosures to run their affairs.

These powerful men may represent the warlords referred to by some Cornish Saints and by King Alfred himself. Successive warlords may have had such command of forces that they were able to resist Saxon advance for so many hundreds of years.

So, moving forward in time to the early ninth century and specifically the years 814-815 AD, we can start to cautiously add detail as this is the time that that the Saxon King Egbert is said to have finally “driven the Wealas – West Welsh –“to the coast. There is debate as to which coast, but if we assume that the general statement is correct and Egbert had progressed his forces this far west, then it is around this time that he set up an estate at the Kilkhampton of today. We should remind ourselves here that this is around 365 years after the various Anglo-Saxon tribes are said to have set foot on British soil following the departure of the Romans; we know that the Western British, the Wealas, resisted Saxon advance for centuries.

With the arrival of Saxon leadership and governance the shape of the village started to take on its modern form. Land was allocated into strip fields for each family; some good productive land other strips less so, but collectively sufficient to provide for the needs of a family. The size of the land allocation was such that it could be managed by one family with some inter-community sharing of work. These strips of land issued out from the central area and can be seen today on modern maps and from vantage points around the village.

The map shows the numerous strip fields around the centre of the village. The image is from the book, “The Making of the English Landscape by Professor W.G.V. Balchin 1954.

There were many such villages preserved in outline today on nearby Bodmin Moor around 18 miles south of Bude.

Some cooperative ploughing, sowing and harvesting were necessary due to the scale of the tasks, which involved teams of oxen to pull the ploughs. The main crops were wheat, barley, oats and rye- the essentials of the day. Of course, cattle also played an important role along with sheep for their meat and wool. Pigs were able to freely forage in the woods as were goats. These animals kept woodland growth under control.

The image shows a typical moorland medieval settlement; the scene at Kilkhampton in Saxon times would have been very similar.

(Impression is of the medieval settlement of Tresibbet, shown with the kind permission of the copyright owners, Bill and Lucy Collis. Financed by the Cornwall Landscapes Project.)

Strategically, the holding of estates at Kilkhampton gave Egbert control of the critical land of what became northeast Cornwall, to the west of the river Tamar. Before this date no invading force could safely cross the Tamar from the east and progress deeper into Cornwall without exposing themselves to resisting forces ahead of them, or from forces issuing off Bodmin Moor or from other defending forces coming in from their rear. all the time escape to the east would become progressively impractical due to the deepening river Tamar. Even with this protection, Saxon settlement indicated by placenames, only ever extended as far as the course of the river Ottery. However, twenty-four years after Egbert’s arrival in our region, the Cornish further west combined with the Danes with the intention of resisting Saxon advance or driving them back across the Tamar. However, as Egbert now in command of the northeast, was able to take his forces south-westward as far as Hingston Down near Callington where, in 838 AD he was successful in defeating the combined Dane/Cornish armies.

Following this defeat, Egbert in 839 felt sufficiently content to hand his Kilkhampton estate over to the Bishop of Sherbourne. Arguably, with Saxon influence and order came greater wealth for this region, compared with settlement farther west in Cornwall. This could also be said of nearby Stratton, which ultimately came into the hands of King Alfred.

During Saxon occupation, the name of the settlement corrupted from the earlier Kylk with the addition of the Saxon “ton or tun ending” So that at the time of the Norman arrival and the Domesday survey of 1086 the village was named Chilchetone, later further corrupted with the settlement or enclosure-meaning term of “ham”. So, we finally have Kilk-ham-ton.

The image summarises the region view showing land and sea trading routes during Roman and Saxon times. The brown watershed route passes down into Cornwall from North Devon with others crossing the Tamar from Exeter and Somerset.

Eventually, as we have seen, the Earls of Gloucester held land here and the Grenvilles set up an estate at nearby Stowe- assuming they did not first settle at the castle itself. The Grenville family would eventually expand Kilkhampton with its church and their great manor houses and the family members acquired fame through their heroism, wealth and power.

See additional subject matter links below and facility to make a one-off website donation.

Also, at the bottom of the links is a further web address which you can copy and paste. This will take you to Kilkhampton Common website- which you can enjoy following a visit to the castle as it is very close by.

Readers may now wish to learn more of the Grenvilles, the anarchy period, the village of Coombe and of Reverend Stephen Hawkers by selecting the history links and local walks by selecting the links below.

If you enjoy reading about our history without any adverts appearing, please help me to meet all the cost with a small donation.

For extra security, the link below will take you directly to a payment centre without an intermediate stage.

For more details of how this donation will benefit you and young local people to our area, please select “info” on the menu button.

Your payment will be much appreciated, however small, thank you.