Bude Canal Walk - Part Two

This walk is another stroll around the canal harbour and basins and continues on from part one of the story, which included the breakwater.

The walk starts at the sea lock itself where Part One also started.

The idea of building a canal had been considered in the late eighteenth century, however, there were numerous problems to over come due to the terrain and small water catchment to support the system. (See The Canal Story).

Eventually, many of the main issues had been identified and on the 14th April 1818 James Green was engaged to review all the previous plans for a canal at Bude and to put forward his own proposals. He submitted his ideas early 1819 and following his formulations, finance for the building of a canal at Bude progressed to the point where his plans were accepted; James Green was appointed as engineer for the project on 23rd July 1819.

But there was a very big obstacle to overcome first in the form of an enormous sandhill covering the whole area from Efford Down across nearly to Ebbingford Manor and to the river Neet at Nanny Moore’s bridge. The sand had to be removed, at least where the canal and the harbour basins had to be built.

The sand hills shown are on the modern beach but it is not difficult to image how this could migrate in land and build up against the cliffs and downs. The hill you see alongside the castle is what remains of this large sandhill.

Green had put forward two ideas for the lock gates; the first was that lock would accommodate vessels of between 40 and 50 tons, essentially large barges that would be beached when the tide was out and filled with sand. When the tide came in, these barges were then floated into the lock and into the canal, from where the same barges could progress to Helebridge, where they would offload their cargo of sand onto smaller barges.

The second proposal, which was eventually accepted, was that a larger sea lock be constructed capable of holding seagoing vessels of 70 to 100 tons. In addition, warehouses could be built Canal side, facilitating general trading of Coal from Wales and other goods from Bideford and Bristol. In the same year of 1819, the Bude Harbour and Canal Company was formed.

Huge numbers of navies were engaged for this work, and many were accommodated in Bude. Many of the men employed were veterans of the Great War.

Despite all the complexities of this enormous project, which included the raising of manpower, logistics of acquiring and installing all the necessary equipment, financing of the projects and overcoming complaints from farmers whose land the canal passed, building work commenced on 23 July 1819.

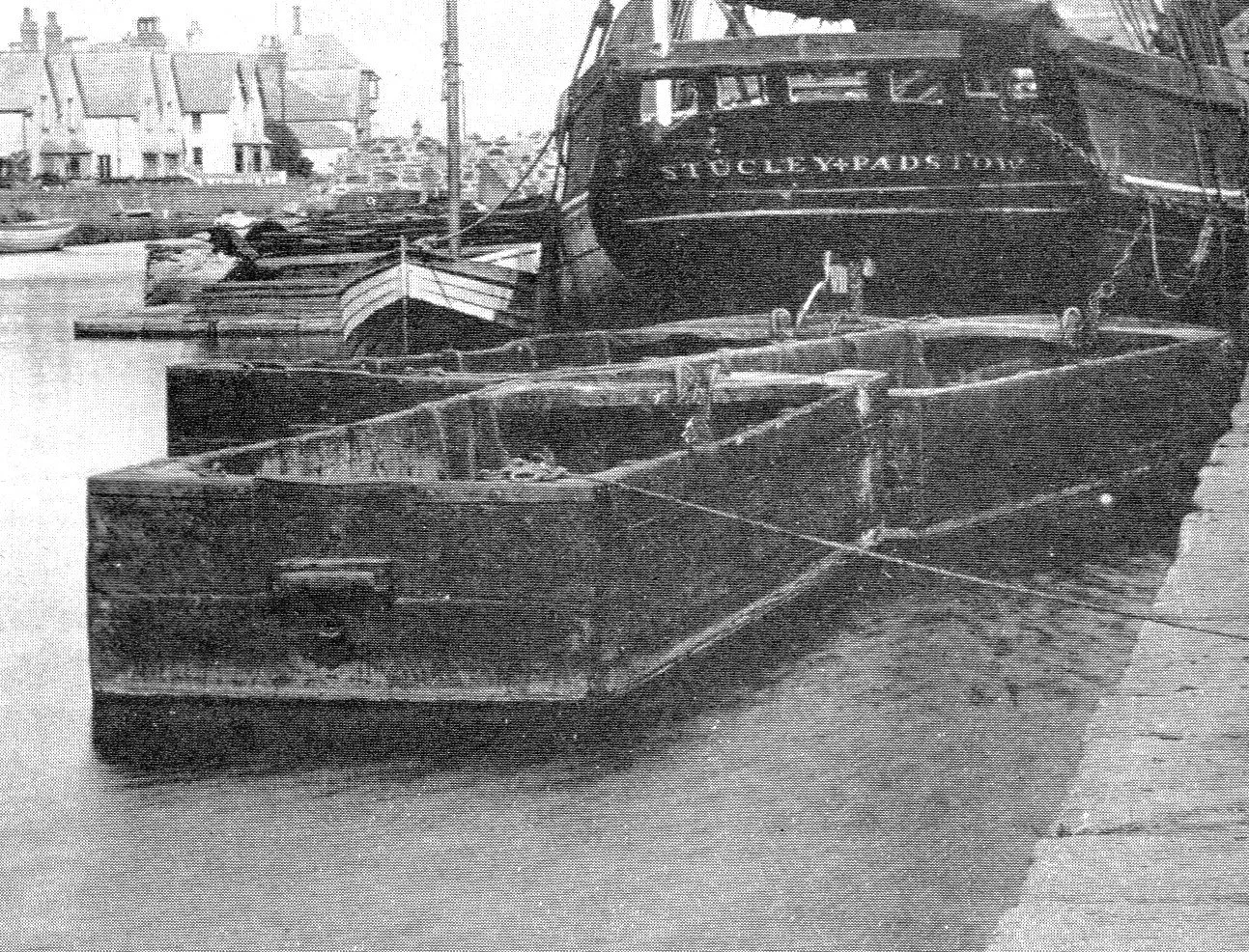

Image shows tub-boats moored up behind one of the seagoing vessels.

Just two years later, the canal and lock gates at Bude had reached the state that some testing could commence.

At this time, it was still planned to transport the sand from the beach to the canal by locking in and out barges and this system was tested on the 21st April, 1821. The report of the time records that, “we took barge No 1 out of the sea lock and (having beached the barge on the sand) put on board her about 24 tons of sand; in the afternoon (as the tide rose) we got her into the basin. It was noted that, “the barge drawing 3ft 6 inches aft and 2 feet 10 inches forward”.

Despite this proving feasible, it was a complex and slow process and also required a lot of water from the canal to operate the locking in and out of the barges. One of the major and influential supporters of the canal was Lord Stanhope and he proposed in April 1822, the use of a narrow rail system going down to and radiating out along the beach. This initially required more expenditure, but the unit cost would be less. This was eventually adopted and instigated.

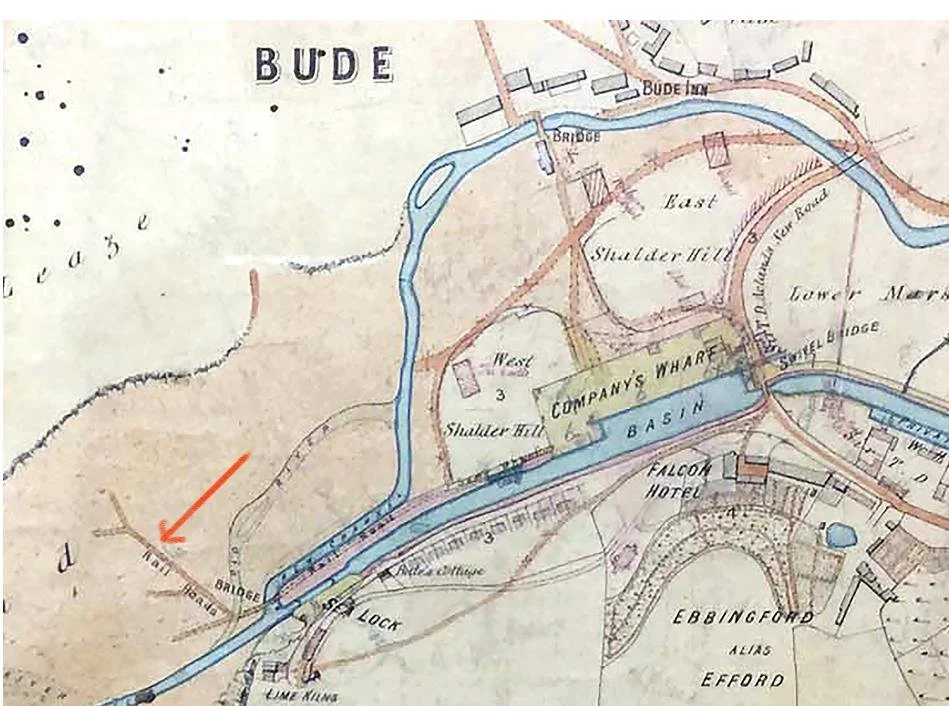

Image shows an early map of the sand rails -arrowed- on the beach.

(Image from the Castle Heritage Centre.)

The actual sand rails changed in design overtime and with operating experience and, to some extent, with availability. It is further complicated by the fact that rails were used early on in the construction of the breakwater, to transport the huge blocks of rocks forming that structure.

Early forms were 4 foot (120cm) “wide L-shaped”, plateway rails; there was yet another “U-shaped” form used. Both these forms, however, had the disadvantage of holding small stones within the form and dislodging the cartwheels from the tracks. It was known that these early rails were used but they had not been seen in living memory until early in 2025 when stormy weather exposed them on the riverbed.

These U-shaped rails did help to guide the trucks at the junctions to ensure they ended up at the canal side. The photo does show what looks like a typical routing junction with a toggle to direct the cart- now locked with rust. It also happens to show a small pebble resting at the junction, showing how it could deflect the wheels of the cart.

After the 1st World War, it is understood that two-foot (60cm) rails were brought back from the trenches and used. These rails had a modern “I-shape”, the same as used on modern rail systems and it is these that can be seen on the incline leading up from the beach.

It is unfortunate that these rails had become slowly dislodged by storms and recemented out of line. Hence one of the reasons for their removal and replacement during the recent summer 2025 work.

Now walk around 50 metres along the canal and looking at the houses on the far side, there is one with a pronounced black frontage. This is the original lifeboat house.

The lifeboat was launched directly into the canal, if the tide was in. At low tides the boat was transported down the slipway and out to the waters edge, where it was launched.

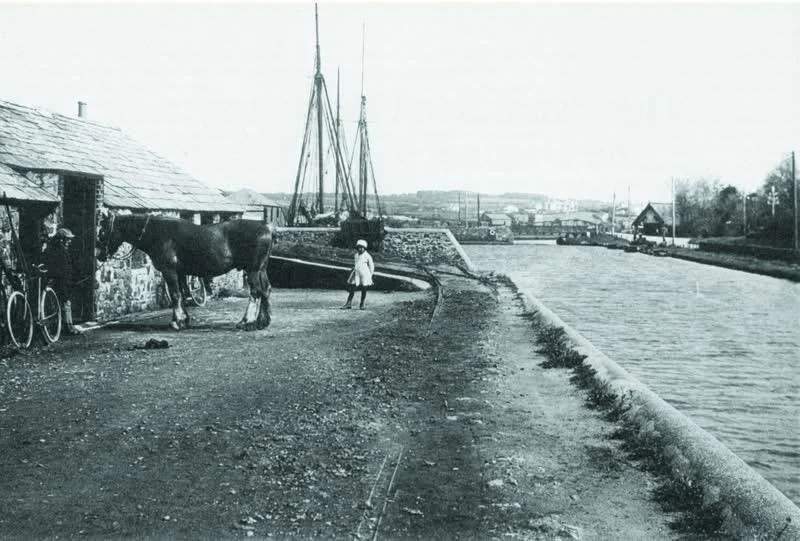

This is a very early Thorn photograph given to the author by David Thorn.

It is interesting to note, the rails heading down to the beach are decidedly wobbly- perhaps they were not distorted by the waves?

Now turn towards the beach and look down on to the new sand rail walkway.

You can see how the new rails have been embedded in to the new concrete pathway.

The photo help[s to see how the new and old rails have been set in the concrete during the renovation work 2025.

Now turn to look away from the sea to imagine the scene when the carts were busy offloading along the canal banking having been towed up to the canal side by a small horse.

This early photo shows the old four-foot rail carts with tipping mechanism that enabled sand to be tipped directly into the barges sitting in the canal. Two horses are seen feeding from two carts tipped to enable them to feed or have a drink.

This later photograph (post 1887) shows the blacksmith’s shop with vestiges of the old rails just visible in the gravel surface.

In the distance is the Falcon swivel bridge and the building with the apex roof is the, then, new lifeboat house which was built in 1863. The Falcon swivel bridge was rebuilt and the canal widened to accommodate the new lifeboat in 1887.

Our walk now moves towards the Falcon Bridge and the area now holding the Olive Tree restaurant. This is the area where in the heyday of the canal the Harbour Company had their warehouses.

Standing outside the Olive Tree restaurant today it is difficult to appreciate the busy scene here in the early days of the canal. There were an average of 220 vessels trading at Bude each year during the period 1825-1900.

The Thorn Photograph shows the numerous vessels in this lower basin abd there will have been more in the upper basin, beyond the Falcon Bridge.

Of course, with the arrival of the rail service, the requirement for coal did not stop. This 1960’s picture show a train crossing the road beside the Falcon Bridge. It was delivering coal to the yards that were part of the orginal Canal Harbour Company warehouses.

The train travelled for a few hundred metres beside the canal having followed a curving path over the iron bridge that leads to the Rugby field of today.

This graph shows the mix and level of goods traded measured on the basis of the number of cargoes transacted on a running 5-year average.

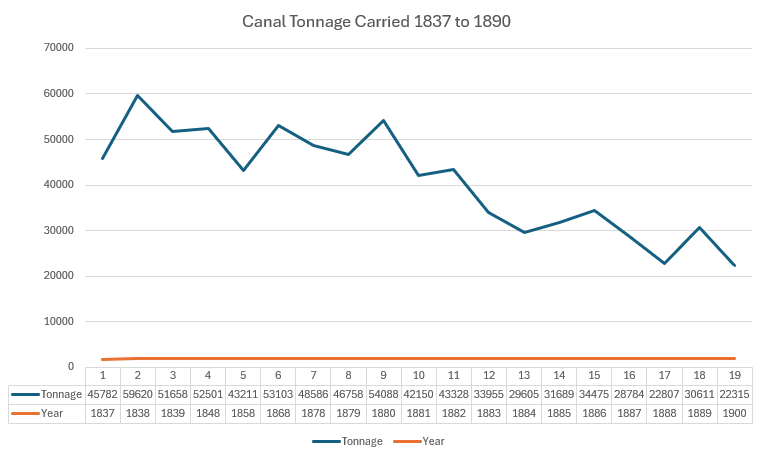

It also, of course charts the steady decline in trade. The arrival of a rail service at Launceston in 1886 and certainly its arrival at Holsworthy 20th January 1879 affected canal trade, as did the introduction of artificial fertilisers (Phosphates) in the 1880’s. If there was a final punch to this decline it must surely have been the extension of the rail service to Bude 10th August 1898.

Artificial fertilizers also affected the use of lime and of culm, the latter had offered a near smokeless fuel in the lime burners. Culm was also mixed with clay and used in homes, especially to give a steady burn during night time.

Culm, incidentally, was mined in Bideford during the 1850’s and 1860’s and surely some will have been shipped to Bude at this time. Of course, our coastline is often referred to as “The Culm Coast”.

As if to reinforce the message of steady decline, this graph shows canal tonnage carried between 1837 and 1890.

In 1880 the graph steepens with the arrival of artificial fertilisers.

This painting shows a large vessels passing through the Falcon bridge cutting. This had been enlarged to accommodate the lifeboat the housed just to the left of this image, but it also enabled these very large vessels to move into the upper Private Basin owned initially by Sir Thomas Acland- another major contributor to the canal initiative and a huge benefactor for Bude from the early 1800’s.

By 1898 the finances of the Bude Harbour Company and the trade on the canal had reached the point where it was a longer viable proposition and moves were made for the Stratton District Council to buy out the shares of the canal with a view to the canal system forming a role in the delivery of a water supply to Bude from the Tamar lakes. This was delayed to obtain royal assent in 1901.

It is interesting to reflect on the fact that it was a need to offer a water supply to Bude that was of interest to the Stratton Council of that time. The idea that it could become a major asset to the town and tourism does not seem to have featured.

For a considerable number of years, the canal has offered boating and other recreational activities, but today it is used for fishing , canoeing, stand-up-paddle boarding, all types of boating. Thousands of young people come to Bude to participate in water based activities and the Surf Life Saving Club use it for training the club members. Of course, all this ignores the aesthetics of the canal and all the wild birds that have also made the canal their home base. A final reflection on this part-two element of the walk that in the sixties there was serious talk of filling the canal with cement to provide car parking!

Part three will follow the canal from the upper basin to Helebridge.

NOTE:

This walk has depended heavily on the work of Helen Harris and Monica Ellis and their book “The Bude Canal” published in 1972. As with all history of Bude, it is also has heavily dependent on the amazing photo archive of the Thorn library and the work of David Thorn today who continues to help the author in developing this website for all.