The Iron Age

The clifftop fort at the Rumps at Pentire

Background

In the opening remarks concerning the Bronze Age on this “pathways of discovery” website, it said that it was a complex subject; this can also be said of the Iron Age. It was a period of significant change, of population growth, of climatic challenges and adaptation to external developments, influences and challenges. All these factors are further complicated by the limited number of archaeological studies carried out locally, that would help to date the Iron Age sites chronologically. Only in recent times has it been realised that there were numerous unenclosed lowland sites, so it can be said that there is much more work to do before a clearer picture of the geographically relationship of Iron Age settlements and forts are understood. However, it is still possible to paint a broad sketch of our Iron Age story based on the work that has been done locally and in the wider area. This article will attempt to explain the cultural structures of our local Iron Age society and how they may have interacted and how the major features to be seen today functioned. This article will be followed with guided walks to some of these features together with details of what is known about each of them. What can be said is that they are all spectacular places to visit and will make for wonderful excursions.

The Iron Age Period

Before getting into more detail about our region, we must first mention a little of the Iron Age itself. The use of iron is thought to have been discovered in what is now Turkey and Syria in the mid-second millennium BC by the Hittite people. They were not keen to spread knowledge of their discovery, but their use of iron appears to have spread into Europe when their Hittite empire broke down around 1180, possibly along with the general climactic induced break up of late Bronze Age culture of that time. It was not until 750BC that evidence of iron working is seen in Britain. Even then, the replacement of bronze for iron tools and weapons took many centuries. The Iron Age could be said to commence around 750 BC in Britain and as the people of our region were little affected by Roman occupation, Iron Age style of life may well have continued with little change during what is described as the Romano-British period.

We saw at the end of the Bronze a deterioration in the climate and this did displace people from settlements on higher elevations. This undoubtedly caused intercommunity friction and societal instability. We are fortunate locally as the North Devon Archaeological Society have done some detailed research at the hillfort of Clovelly Dykes and this has shown that the inner ramparts of that fort were of a defensive nature and slingshots were found in that location. Progressively, in the later Iron Age, developments within this fort suggests that society found a way to live together, despite the climactic challenges, and the site was enlarged with banks and ditches plus a kraal, clearly for cattle handling, rather than defensive. Gabbroic pottery from west Cornwall is found associated with this later phase, demonstrating local trade. This fits with classical accounts that speaks of cattle and hides being a major export.

This tells us how life in the Iron Age may have evolved in our local region; unsettled at the start due to climactic challenges causing instability and localised fighting. As societies resettled in new locations and found ways of supporting their families then, with time, they began to find collective ways of working together in major projects, trade and exchange.

Based on Cunliffe, Britain Begins

Cultural Types by Region

Perhaps it is no surprise that Iron Age society in Britain did not develop in identical ways, either due to external factors, terrain differences or geographical location. Southern Britain, for example, has been divided by one archaeologist into three economic, or cultural zones. It is suggested that the central zone and possibly the eastern zone were able to produce an excess of produce which they redistributed elsewhere a so-called “Redistributive Economy”. These two areas, being closer to the Continent, arguably shared in a greater cultural exchange and influx of ideas, some of which may have filtered through to our region. The central region or zone also appears to have had a more hierarchical structure with very large forts, compared to those in Cornwall.

In what is termed the western zone, which includes Cornwall and Devon and at least South West Wales, here was arguably a more co-operative society of producing and consuming communities, with some organising structural hierarchy. It is possible that this involved smaller agricultural producing settlements; what they produced may have been dictated by their location and soil – that is coastal, hilltop, valleys, south-facing slopes etc. It is also conceivable that some localities took on specialist tasks such a metal working. A metal working site at Duckpool is known to have existed at least into the Romano-British period. All this suggests a society that was interdependent of each producing community. This is borne out by dozens of promontory forts and a number of larger forts; all of which required the community to build, collectively. There are just too many small forts for a true hierarchical figure at each site. Nevertheless, the term given to this western cultural zone as a “Clientage Economy”. That is, two broad groups; a group or community who provided goods and produce and those of a second group, representing a consuming community of higher status. This simply does not seem to match what is seen locally, but that is for the reader to judge from what follows.

Broad Regional Differences.

It has already been stated that southern Britain, being nearer the Continent had a larger influx of people and ideas; this was particularly so in the late Iron Age period when there is evidence of a large mix of traders, people movements, mercenaries and traders. South Cornwall was the centre for tin production and trading, possibly from St Michael’s Mount. Also, in the far west of Cornwall, pottery was produced using the local gabbroic rock, which was widely distributed throughout Devon, Somerset, Hampshire and Northamptonshire. Also, south Cornwall was directly involved in coastal marine trading. And there was a direct trading link to Brittany at Mount Batten in the Tamar estuary. So, the question is, what of our local region?

Image is of the promontory trading port at Mount Batten, South Devon from where Bronze and Iron Age produce was shipped to the continent.

Red circle are the three large multivallated forts; blue arrow represent the tidal flows along our coast; the green dots, the possible inland tracks and, finally, the purple dotted line the watershed running down through the region, avoiding valleys and Bodmin Moor.

Landform in our local area which will have defined the nature of local cultures and their produce.

We will start by looking at the broad physical geography. The land was basically an early marine platform that has been eroded down by rivers, with patches of high ground, major moorlands and all exposed to the forces of the Atlantic and its climate. Of course, running through the whole region is the Tamar River and valley, providing a trading route to and from the Channel. The watershed that runs down the spine of our region passes through our area and must have provided an obvious track or route, avoiding the endless coastal and inland valleys. It seems logical that there would also be something of a land route to the east, towards modern day Exeter, avoiding the obstacles of Bodmin Moor, Dartmoor and the deeper water sections of the Tamar. Along our coastline we have the Camel Estuary, Boscastle Harbour and, in the Iron Age, the estuary at Bude and the Taw/Torridge estuary to the north. Our coastline was a major Atlantic coastal trading route, conveying trade to all of western Britain and Ireland, and down the Atlantic trading regions of mainland Europe and the Mediterranean. Plus, it was part of the southern coastal trading routes of southern Britain.

In the top North Devon region is the Iron Age fort of Clovelly Dykes set on high ground. Centre is Warbstow Bury, North Cornwall, set on high ground and circled by the River Ottery. Finally, in Restormal District, is Castle An Dinas, again set on high ground with local water supply.

Diversified Landscapes

Within our region we have such diverse landscapes as the comparatively dry, but windblown, coastal cliff-top land; there is the clayey Culm Measures to north and east; the poor quality lower moorland of North Devon; in the hinterland we have sheltered river valleys with numerous spurs of higher ground and, for summer grazing, we have the higher elevation lands of Bodmin Moor- which were also major centres for festivals, rituals, gatherings and trade.

These natural barriers and diversified landscapes may well have kept our region free of some of the developmental and cultural influxes that could have negatively impacted on other regions. The relative isolation of the region may have left it free to pick and choose ideas that suited local needs and remain detached from influences that did not suit. The region was something of a throughway and a significant component of maritime trade throughout western Britain, providing many safe havens on an exposed coast. It could be argued that a lot of communities would have a vested interest in keeping this region stable. One writer rather succinctly put it, “its communities developed along individual lines, influenced more by the structure and food producing potential of the land, than by external stimulus”.

So, it can be said that our region, with such diversification of landforms and land uses, may have been able to develop a greater degree of produce autonomy, but with interdependence between localised communities. Such interdependence will have necessitated cohesion, planning and leadership; no doubt some of that cohesion coming from involvement in major community projects, such as building huge hillforts. The southwest peninsular of Wales has similar landforms to our region and has been subject to fairly detailed studies which identify cultural similarities with our own region, and this does help us to understand our local area.

So, with this knowledge, we will now review in broad terms some of the major features of the period:

Each Prehistorical period leaves its mark.

Each period of pre-history leaves us with something physical, tangible, of the period: flint artifacts, dolmens, stone circles and alignments, burial barrows and round houses. And surely, when we think of the Iron Age, our minds link to the great Iron Age forts. Locally, the Iron Age communities also left lowland settlement “rounds”, comprising small communities or even family units, plus coastal promontory forts and small hilltop enclosure settlements. Each settlement had a role in this complex society and each community or extended family unit would have been interdependent. The complexity of need and trade would require some degree of local leadership, plus specialist skills or tradesmen.

We will now try to contextualize these features and place them within the cultural and physical dynamics of the times. It is very frustrating to visit these significant forts and settlements and have no concept of how they functioned or of the role they played in the lives of the people who built them. We will start by looking at the possible role of promontory forts.

Promontory Forts.

It is impossible to walk the coastal paths of Cornwall and North Devon without encountering a promontory fort. There are at least sixty-six known or identified on the Cornish coast alone. (See the image opposite)

The first thing that should be said is that these were not fortifications beyond which the community retreated when threatened by some external force, nor were they the home of elites. There would be an awful lot of elites were this the case, but also, these windy promontories were not comfortable places to set-up home. We can only postulate their function based on the needs of the community, the community interaction with others and the physical characteristics of the environment in which they are situated.

The proposal is that they were first and foremost multi-purpose trading posts. Let’s look at the context. The local seas were the trading highways up and down the western coast of Britain, to the Continent and down to the Mediterranean. This is the Atlantic Ocean, which can throw up storms, strong winds and big waves with little warning. The filling and emptying of the Bristol Channel generate strong tidal flows along our near shore; the flows being south to north as the tide rises and the opposite on the ebbing tide. This renders rowing or sailing small and large boats and ships near impossible, especially if accompanied by strong winds.

Equally, the ship and boat masters could take advantage of these tidal flows to aid their progress, resting their crews when the conditions were not favourable. The mariners may be trading quite locally, or trading the complete length of the western seaboard of Britain; plus coastal trading along the English Channel ports and some will be trading the near Continent and the Mediterranean. Some ship’s masters would know the coast and their rocky dangers, the safe havens and estuaries, others would not. It was by these shipping routes that trade was conveyed to all the scattered communities. It was not practical to travel across country carrying large quantities of goods, for practical reasons and security. The boats ranged from those of the Irish style Currachs, having wood frames covered in a tarred canvas, to the great Veneti sailing and oared ships of Brittany and to those of the Phoenician Mediterranean trader ships which carried some sail as well as numerous oarsmen.

Progress along our shores.

These ships and their crews needed regular provisioning, possibly carpentry and metal-smith repairs, occasional shelter and navigational guidance. The local communities needed to exchange their goods for products from elsewhere. It was in the interest of everyone that this trade functioned safely and efficiently. This Google Earth image shows the nightmarish nature of our coast, studded with island and dangers. Continued next page.

Courtesy of Cornwall Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB); it is possible that the third bank and ditch on the landward side is Medieval.

We can now imagine a community deciding they needed a trading port and coming together to collectively construct such a facility on their local promontory. Across the narrowest part of the promontory, they build one or more banks and ditches, possibly with the addition of a gated palisade. This looks like a fort and to some extent that is what it was. The community wanted to ensure the goods held. or stored, at their port, awaiting a trading ship were secure and when valued goods were received off the ships, they too were secure until they were distributed within the community. We should remember that the timing of these trading vessels must have been something of an unknown, so goods to be exchanged were held for long periods of time, which made them vulnerable to small marauding groups from the land or sea unless well-guarded. So, these forts could also be guarding the front door to the community, so to speak, with a rotating cohort of guards offering permanent protection or forewarning of danger.

On the positive side, the progress of trading boats would be greatly aided by some form of signalling and, presumably lighting at night – a chain of beacons along our coastline? Someone signalling that the community wanted to trade?; maybe also having something that informed the mariners of the facility, that it simply offered shelter or was part of an estuary?

Again, looking at the image, if one of these promontories had agreed to trade, how could the captain of the trading vessel know which one to call at? These are questions to pose when visiting these site and, hopefully, in time further research will provide more detail.

However, these were uncertain times; ships with numerous men on board may be honest traders or a potential threat. They may appear friendly but may have other ideas if they were given easy access inside the fortifications. So, we can appreciate a need for caution and strong defensive to protect hard earned products.

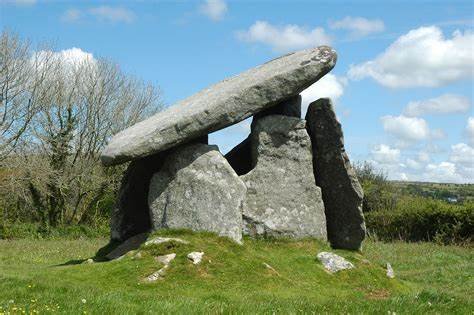

This is the isthmus leading to the clifftop fort of the Rumps. The earth banking and ditches are seen here at the entrance where there would have been a palisade. The exposed coast can be seen but just to the right of this picture is a sheltered cove. Such forts are very exposed and would not make for comfortable long-term settlement with no water supply - not a sensible refuge!

How the Trading Point may have operated.

We can now imagine the arrangement at the community trading point. The place has been made secure, there is a constant level of manning, storage areas and accommodation are built and there is a contingent of guards and people assigned to conduct the trade. Most trade will have been conducted during the farer summer months and animals, mainly sheep, would have grazed the local pastures during the day; being taken back within the palisade during the night to keep them out of reach of rustlers and wild animals.

If a passing ship needed provisioning the captain may bring his ship within the shelter of the promontory and goods and provisions exchanged. A metal smith or carpenter may have been on hand to provide a service. We can imagine that this interaction may have taken place outside the bounds of the secure palisade with guards looking out over the balustrades. Equally, if the community had goods to trade or needed goods, they may have had an agreed signal to a trading vessel to call at their port. At night we can imagine that each promontory lit a beacon to guide ships along our coastline.

Saint Piran’s Round, Cornwall. Courtesy Heritage England

Settlements “Rounds” and small Hilltop Enclosures

If you have read the story of the Bronze Age settlements on Rough Tor, Bodmin Moor you will have noted that the simple round houses tucked into edge of field systems had evolved into small communities of round houses, surrounded by a stone wall. When the climate deteriorated settlements on the Moors were largely abandoned but the idea of enclosed settlements was taken by these people to lowland and sheltered inland valley sites, where the surrounding enclosing wall comprised mostly of an earthen bank and ditch- although some may have used a wooden palisade. Each enclosure may have comprised a clan-group of certain skills, a large family or simply a community of diverse people. The enclosures were on lowland sites and on the upper spurs of valleys. Some were literally on hilltops. There were also numerous unenclosed settlements, although evidence for them is still coming to light. They may be described as mixed farming in nature with a mix of crops grown. The principal varieties of crops were emmer, barley and spelt wheat. Each of these grain types were suited to different soils and seasons, so the diversity of landscapes would give each settlement a value to a wider community. Less frequently grown were rye and oats and occasionally, flax. Beans were also grown, and these may have been valued for their ability to enrich the soil – we now know by their nitrogen fixing qualities.

Within some of these settlements were grain storage pits, raised storage areas for processed cereals, querns to grind grain and spindle whorls. Cattle, sheep and pigs were reared, appropriate to the location. The wool of the sheep was possibly more important than their meat; the sheep being similar to the ancient Hebridean types, such as the Soays. Cattle may well have been use as beasts of traction as much as for their meat or milk produce.

Our walks will identify a range of such sites and will include details of known finds within them. In this way a clearer understanding of their location and function will become clearer.

Large Hill Forts.

There are numerous forts dotted around our region, some smaller ones identified as camps. However, here we are thinking of the really large forts of our region, mostly situated on highly visible hilltops. They are not as large as those to be found in southern England nor as numerous as central areas of southern England and up through eastern parts of Wales. We have one large fort in North Cornwall, Warbstow Bury and nearby at St Columb Major, Restormel, we have Castle An Dinas; in North Devon, we have the large fort at Clovelly Dykes. It should also be mentioned that there are two other smaller camp/forts to the west of Clovelly and one more locally on Stamford Hill, Stratton; the latter being the chosen by the Parliamentarians as site for a significant battle during the Civil War (May 1643), a battle where the local Cornish Royalists were victorious.

The map opposite shows the geographical location of these forts in relation to landforms, possible land routes and Atlantic shipping routes. (Red dots)

The visibility of, at least, Warbstow Bury and Clovelly Dykes were enhanced by white granite banking- they were meant to be seen from afar. One of the purposes of the forts clearly was to be seen from afar. It was a statement of territorial ownership and maybe a symbol of local achievement and cohesion. These forts may have started as smaller hilltop enclosures dating to the Bronze Age. As populations grew during the Iro Age they were enlarged significantly and their function evolved. Warbstow Bury and Castle an Dinas do not show much evidence of permanent dwellings. But recent studies at Clovelly Dykes in North Devon has shown evidence of continued occupation throughout the Iron Age.

It can be said that the hillforts of Cornwall and North Devon continue to reflect regional differences. Those in south Cornwall are not situated on hilltops and, not surprisingly, given that the County narrows westward, they tend to be mainly coastal. Here in North Cornwall, including Castle An Dinas (Restormel), the multivallate forts are situated on prominent hills, whereas the large fort at Clovelly Dykes is on high ground, but not a hilltop – albeit commanding significant views.

Warbstow Bury and Castle An Dinas have concentric earthen banks; that of Clovelly Dykes, circular at the centre, tending towards rectilinear on the western side. (See later Image.) Some forts have evidence of continuous occupation others transient. Clearly, the communities developed these major facilities to meet their specific needs.

If there are common themes it might be said that they all represent an important societal function and a significant physical community commitment in which they could all have pride. The forts were probably used for animal husbandry, which may have involved breeding exchanges and those nearer to the Bodmin Moor, even preparation for summer transhumance to higher grounds. There is general agreement that they were used for celebrations, feasting, storage and trading and it has been suggested, presented opportunities to display power through the wearing of ritual regalia and weaponry; there is evidence of ritually broken weapons being deposited, and this may account for evidence of metal smithing. Many sites do not show signs of permanent settlement, supporting the special occasion theory, and this includes Warbstow Bury and Castle An Dinas.

Image, courtesy Heritage England

Our Twin Region of South Wales

A detailed study was carried out in coastal areas of south Wales, at six locations, and it was shown that there were facilities for cereal storage and redistribution. It could be that cereals grown elsewhere were processed, stored and then redistributed. The general sense is that all these were essentially trading centres of one kind or other and it has been suggested that they were precursors of Mediaeval Market Towns.

When more detailed studies have been done on our local forts and enclosure rounds then we archaeologists will be able to provide a more comprehensive picture of the different cultures that prevailed in our region. In the meantime, Warbstow Bury and Castle an Dinas are a “must visit” location as they are magnificent examples of hill forts and dominant location.

Clovelly Dykes is in private ownership and permission must be sought before visiting. But it is an interesting part of our story. It is built on high ground but does not command the same hilltop location as others, although when built it is possible that it could be seen from the sea. The surrounding land was not of high quality and may have been more suited to pastoral activities. However, there is some evidence to support cereal growing where soils permitted. It was therefore a mixed economy, but with some emphasis towards animal husbandry. This may account for the way the fort at Clovelly Dykes evolved, being very much a centre for coastal trading and the exporting of animals, possibly like those of southern Cornwall. Clovelly Dykes and the nearby Embury fort, which is also very much coastal, both have evidence of Gabbroic pottery attesting to coastal trade with southern Cornwall.

Image courtesy of North Devon Archaeological Society

The steep valley enclosure of Stowe Wood and Coombe Valley. The large red circle shows the location of the Iron Age settlement, set, typically, on the a spur in the valley structure. Image, courtesy of English Heritage.

Duckpool and Coombe

We can summarise our local area as a very mixed economy of diverse settlements, scattered across a mixed terrain of variable soil quality, elevations and micro-climates. However, the interdependence of the communities brought them together, self-supporting and creating major structures that gave cohesion to the community but also serving important functions of trade, feasting, celebration and possibly support and security during stressful times. Just to the north of Bude is the valley of Coombe and Duckpool and this location seems to encapsulate the above summary.

The whole valley is surrounded by steep hills to north, south and east; at the seaward end is a narrow opening to the beach. The valley sides inland are wooded and on the southern slopes are valley spurs. On one of these spurs is a small, fortified, enclosure. That is that houses were surrounded by an earthen bank and ditch, the site to west, south and north is precipitous, but the eastern entrance is comparatively flat ground; here at least would require a palisade and entrance gate, if it is truly to be a fortification. On the lower areas of the valley there is little suggestion of field systems and unless they were growing cereals, which is unlikely, there would be little need of fields. Whatever animals were held by this community they were free to roam the valley floor and unwooded sections of the hillsides, but they were essentially, contained by the enclosed form of the valley topography. Even if there were communities engaged in marauding, they would have difficulty in extricating the animals from this valley. It is also possible that the animals could have been corralled in an enclosed area at night, to protect them from wild animals, as much as from marauding groups.

This image is of the earthen embankment of the Iron Age settlement, set on a spur within Stowe Woods, Coombe Valley. Still mystical.

At the seaward end is a narrow opening to the sea and, certainly in later Romano-British times, the people of this community were engaged it metal working on an industrial scale, with raw material being shipped in from probably from north Somerset via the Bristol Channel coastal trade. It is in this later period that the people of this small community learnt to produce a purple dye from Dog Whelks, a process developed by the Phoenicians of the eastern Mediterranean! Surely, this demonstrates the resourcefulness of these communities and the degree to which they adapted their lifestyles and productive output to match their location, environment and terrain to maximum advantage. This also demonstrates the huge potential for diversification across our local varied landscape and is further proof that is not possible to be too precise about the nature of Iron Age communities across the greater region of the southwest, including parts of Wales.

The view opposite is little changed from that of the Iron Age and the steep enclosed nature of the location is self-apparent.