Bude Canal History

Early History of Sand Use

It is almost impossible to write the history of Bude and its harbour without reference to the sand of our beaches and of our terrain; sand and terrain very much applied to the story of our canal.

Richard, Earl of Cornwall, had given local inhabitants the right to take sea sand from the beaches in order to raise the fertility of their lands. King Henry the Third confirmed the rights. His charter in 1261, states, “our dearest Brother (Earl Richard) has granted for common benefit of all Cornwall, in all lands of the King and his men that they should have and take the sand of the sea. The charter goes on to say, “they may also freely heap the sands upon their lands by such reasonable roads assigned to them, or to be assigned”.

The picture shows the canal near the lock gates where the sand was loaded onto the barges. Before the canal was built in 1823, all that you can see in this picture was a mountain of sand. This had to be taken away before the canal was built.

But there arose a problem; the incised valleys along our coast and the dissected, wooded and, in places, boggy plateau land of the interior, made it very difficult for wheeled vehicles to operate. Transportation by packhorse was the only option. The map shows the high ground and numerous valleys that made the route for a can so difficult.

In 1774 the idea was conceived to build a canal across this difficult terrain but it would take until 1817 for engineer James Green and surveyor Thomas Shearm to be engaged to survey a possible route. Two year later the project commenced and the first section to Holsworthy opened July 1823.

The background story of this canal now follows but, in due course, a guided walk will be added to this site which will provide more details at each location.

The Grand Idea

We are grateful to the Bude Canal and Harbour Society in the preparation of this story and the map shown is from the Bude Canal Regeneration Project undertaken by the Bude/Stratton Town Council.

The thick red line shows the route of the canal that was finally built. It is a sad fact that the southern route did not quite join up with the lower reaches of the Tamar, as had been hoped, and the eastern route was somewhat truncated just to the north of Holsworthy.

Early correspondence had conceived the grand idea of the eastern route eventually linking with the canals of Bristol and beyond. It took just too much time to resolve the difficulties of the terrain and the shortage of water catchment to operate lock systems.

Poor Soil but High Quality Lime-Rich Sand.

Our geology is a complex of repeating shales, sand and granite, each producing challenges and opportunities for the farmer and the soil’s ability to provide for the needs of the people. The slatey soils were highly productive for barley and wheat, but it lacks one important element, lime. Before the age of modern artificial fertiliser, the abundant harvest of wheat and barley could only be satisfied by the addition of sea sand. In fact, the importance of Bude sand and the ability of our farmland to produce wheat and barley cannot be overstated. Written into the farm tenancies were clauses which stipulated precise details of crop rotation, with a standard clause, “upon every breach for Tillage shall carry 8 Butt or cart loads of good sea-sand or 100 Bushells of well burnt lime; and shall mix the same with eighty Butt of good Dung Earth and other manure, according to the rules of good husbandry”. And so it was that whilst the sand at Bude created so many problems for its harbour, it was also a great asset. Its high shell content was highly valued. It is difficult to imagine how Bude would have evolved were it not for sand.

Picture shows the repeating nature of sandstone, siltstone and shale bands that outcrop in the fields around our region. The various rock types broke down over time, due to the action of normal weathering and the shales, particularly, washed out, to accumulate is hollows and valleys resulting in shaley poor soils.

Background Story

But transporting sand in small quantities by packhorse across our hills and valleys was an expensive and inefficient process. Wheeled transport was tried but this caused its own problems of damage to the very poorly surfaced trackways and the damage had to be repaired at cost to the local communities. Picture shows vestige of the old sand road at Bude.

Writing just before the opening of the canal T. Moore, “History of Devon” writes, of the beach of Bude, “it presented a very animated scene at each low tide during the tilling season, being thronged with wagons, carts, packhorses and herds of mules, loading and carrying off sand to the interior”.

Another author writing in 1796 remarked on the use of packhorses and the absence of wheeled carts. He writes “lime is universally carried in sacks slung over pack saddles”. On arriving at Tiverton in Devon the same writer observes, having travelled through the whole of North Devon, “seen several wheel carriages, carts and wagons, on this road. This is the first I have seen on this journey”. It was obviously, a rare sight worth recording in his diary.

It was clear to the community leaders that a solution had to be found and the idea of cutting a canal through this improbable landscape was born. A local Cornish man had already constructed a canal at St Columb, and he put forward a plan for a canal from the Port Harbour at Bude to link with the River Tamar at Calstock. The idea was to convey not just sand but Welsh coal, stone and lime, plus other manures, mining products, timber and agricultural goods and domestic supplies. However, there was the problem of terrain; it is 28 miles from Bude to Calstock, but the planned route was so circuitous that the total canal length as proposed would be 90 miles. This was deemed too costly, and the search was on for someone who could develop a plan that would overcome the many problems, but also be beneficial to many communities at minimal cost. Lots of plans were developed but did not win the confidence of the investors and the Government, who were contributing significant sums of public money to the project.

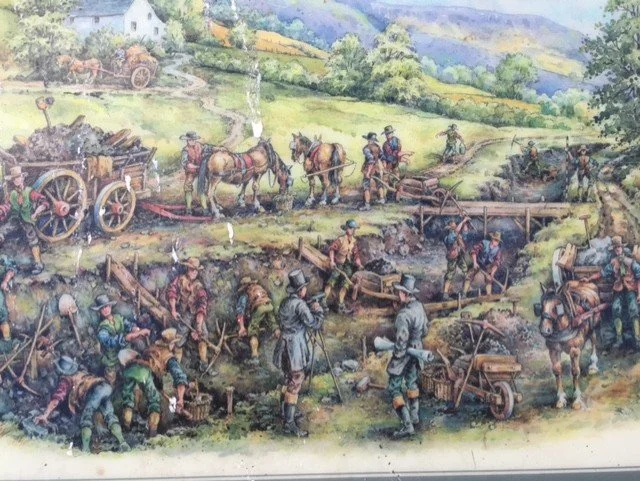

The image shows a canal being built near Ludlow in 1821. This gives a sense of the hard manual work involved.

The Idea Takes Shape

It would be a further forty-three years of deliberation until, in 1817, engineers James Green and Thomas Shearman, were invited to carry out a survey which would include taking into consideration all the good and bad points of earlier submissions. Their scheme had to overcome the big problem with our region, namely a small water catchment with no significant rivers to feed lock systems that would normally be necessary to overcome the numerous changes in height.

The map shows the feeder arm of the canal at Tamar Lake built as a water catchment reservoir to overcome lack limited water supplies.

Image from the Regeneration Report commissioned by Bude Stratton Town Council

Rounding The Barrel in a Nor Wester; painting by Roger Adams of Bude. Image owned by author.

There was yet another significant problem to be considered; the Port of Bude itself. The harbour was exposed to the full force of the Atlantic making it extremely dangerous for vessels to enter, to be anchored in and to leave the Port of Bude. To be truly successful in expanding trade, to maximise the use of the canal and give a return to the investors, this problem had to be overcome. Photo shows the drama of entering the harbour at Bude even after the construction of the breakwater.

The breakwater was built with vertical sides as if defying the forces of nature. It did not last long. A major storm in February 1838 blew holes right through the structure and it had to be redesigned by the Companies resident 2nd Engineer, George Caseborne. He had been in the Canal Company’s employ since 1832 and would remain in this position until 1876. His redesigned breakwater is the one we see today and, of course, it presents a curved face to the waves.

Image of George Casebourne on next page.

Work Begins

James Green was eventually selected as First Engineer for the project, and he presented two plans to subscribers in April 1818. One scheme involved a conventional railway system, but he saw many problems with this, principally the many hills to negotiate and the underlying soil- not to mention expensive viaducts. He favoured a less ambitious canal using small tub-boats and incline planes; the small tub-boats, capable of carrying 5 tons of sand or goods being raised by water-powered mechanisms. Four of these small boats would be linked together and pulled by one horse. The first two miles from Bude to Helebridge would involve a wider deeper canal with much larger barges carrying up to 50 tons of sand or goods. He estimated the cost of the completed project at £128,341. That is within a few thousand pounds to £14 million today. His ideas were generally accepted, but his original ideas were cut-back further to bring the total costs back to £91,617, or £10 million. Once agreed the principal subscribers wasted no time. A Parliamentary Bill was enacted on 14th June 1819 and the Bude Harbour and Canal Company was formed with Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, of Ebbingford Manor, Bude one of the leading shareholders and, of course, a principal landowner through which the canal would pass. Work actually commenced on 23rd July 1819.

Image is of George Casebourne the 2nd Engineer.

Linked tub-boats seen here on the lower basin at Bude near where they and the larger 15m X 4m barges were filled. This proves that it was not only the large barges that started the journey from the Port. Of course, the larger barges, which carried around 50 tons of sand, were off-loaded to the smaller tub-boats at Helebridge.

This is the location of the Sampson’s Boat Hire of today.

Changes and improvements would be made as the project evolved, but the project when completed would include: a wide and deep canal at Bude accessed from the sea by a large sea lock capable of handling vessels of up to 100 tons.

There would be two major wharfs, the Lower Company’s Wharf and the Upper Private Wharf.

Seen here is the Lower Wharf-just to the right and out of picture were the coal yards.

The first section of the canal after the lock gates was used to marshal the vessels waiting to leave the port or to enter the two main wharves. Also, this area served as the barge loading station for sand taken from the beach.

The Upper or Private Wharf was owned by Sir Thomas Acland; one of the principal supporters of the project and on whose land the Bude section of canal is built.

In this image, just beyond the building with the chimney is Stapleton’s Boat Yard, where many of Bude boats were built. One can be seen surrounded by props.

One of the changes to the original plan involved the construction of the narrow-gauge railway from the lower wharf near the lock gates at Bude. The rail line led to an iron bridge and further rails spanning out across the sands of Summerleaze Beach. In fact, the gauge of these rails were upgraded in 1923 to what you see remnants of today.

Horse drawn wagons transported the sand from the beach to the wharf where the sand was loaded on to large 15m long by 4m wide barges - and sometimes onto the smaller tub-boats that would be used from Helebridge and onwards. At Helebridge, the larger barges transferred their cargoes on to the smaller tub-boats ready for their progress to the interior.

However, some farmers preferred not to pay for the sand to be conveyed further inland to their farms and collected the sand from the larger barges at Helebridge.

A Complex System of Incline Planes

The canal system included six incline planes using different forms of waterpower. The small tub-boats had wheels which enabled them to be pulled clear of the water onto rails easing their progress up the inclined planes. The first incline raised the tug-boats up the hill from Helebridge to Marhamchurch from where they progressed to Thurlibeer and the large incline at Hobbacott Down; then on to Red Post, where the canal split into two directions: one north eastward towards Holsworthy and Blagdonmoor, the other south eastward towards Launceston, terminating just beyond Druxton Wharf near Launceston.

Photo shows section of the canal at Rodd’s Bridge, one mile from Bude.

Image shows the upper and lower basin; plus the line of the river and towards the sea the breakwater.

This is the scene at Helebridge where the large Bude barges unloaded their cargo and transferred the sand to the smaller tub-boats for onward progress along the complex of canal-way and incline planes. This is also the location of the Barge Workshop Museum of today.

Scene from the book of 1972, “The Bude Canal by Helen Harris and Monica Ellis. (See books from menu.)

Unique Systems of Operation

The total height gain from sea level to the highest point near Holsworthy was 132m and the Launceston branch descended from its highest point of around 114m down to 63m. The Marhamchurch incline raised the tub-boats 35m over a distance of 251m. An overshot 15m water wheel at Marhamchurch pulled the small tub-boats up this incline, whereas at Hobbacott, which was the longest incline, this utilised a novel “continuous chain system” driven by waterwheels, plus two huge buckets which were filled with 15 tons of water. This was known as a, “bucket-in-well” system. The buckets when full descended down a deep well (69m deep) and in so doing rotated a drum which in turn pulled the barges up the incline using a very long chain. A pin at the bottom of the well emptied the bucket of their contents which discharged via a Leat. An empty barge returning to Bude descended on a second rail and this helped to pull the laden barge up the incline.

At Red Post the canal branched; one route towards Holsworthy and the second towards Launceston. The image here shows the route passing through the incline plane near Vealand.

At Helebridge the water of the River Neet and two smaller rivers were diverted into a single catchment to supply water to the Bude section of the canal; this incorporated an overspill weir (in picture) which permitted a continued supply of water to the River Neet as it flowed towards Bude.

Combating The Power of the Sea

With the building of the breakwater at Bude, providing protection for the harbour and the entrance to the lock gates. Even today, with the breakwater in situ, the lock gates can be damaged by storm waves and they have to be supported with large wedging stays.

The course of the River Neet was also changed to channel the river flow towards the newly constructed lock gates and out to sea at the extremity of the breakwater. The river flow served to keep the channel clear of sand and, along this channel, were a number of posts that enabled the large vessels to be warped into the inner harbour where they bottomed out as the tide ebbed. The map shows the redirected river course towards the canal sea lock.

Below is an image of the first breakwater with banjo pier, destroyed in a storm in February 1838.

At Helebridge this house was built for the 2nd Engineer George Casebourne and he lived here throughout his time with the Canal Company, until his death in 1876.

The image shows the house at that time and it can been today when you visit what we call the Barge Workshop. In fact, the workshop was a warehouse and was not built until 1838-40.

Work on the canal commenced on 23 July, 1819 and hundreds of navvies were hired to work on its construction. This was in the early post-Napoleonic period when there was a need to find work for the survivors of the wars and we know that Sir Thomas Acland was particularly keen to create employment for local people. There were great celebrations at Bude and Holsworthy at each stage of development. The section from Bude to Holsworthy was completed in July 1822 and the whole system was completed in 1825. There were many problems with the complex machinery, financial difficulties, legal battles with some farmers, problems with mechanical failures but there were periods of successful trading. Eventually, the London & South Western Railway reached Holsworthy on 20th January 1879 and this impacted on profits and the pockets of investors who still had to prop-up a complex canal network that was suffering from fatigue of mechanical components and servicing the upkeep of the extensive embankments. On the 10th August 1898 the rail line to Bude was opened and this led to the ultimate demise of the canal. There followed a few years when ideas were proposed to utilise both rail and canal collaboratively but ultimately the Stratton and Bude Urban District Council bought the entire operation for £8,000. Part of the plan was to utilise the water held at Tamar Lakes to serve the needs of the community. The Bude Harbour and Canal Company was finally wound up in March 1902 with the repayment of £4 per share to Shareholders.

Bude Built on Sand

There is a tendency to judge the canal in terms of financial success or failure. This would grossly underplay the achievements and determination of the engineer James Green and the people who operated and maintained the canal, not to mention the financial risk taken by its financiers. As one writer put it, “the Bude Canal was surely one of the most extraordinary institutions in Rural England”. The region offers a totally unsuitable landscape for a canal that could ever be imagined; a highly dissected plateau land in an underpopulated corner of Cornwall and Northwest Devon. Yet the local leaders and financiers were determined that it should be built to the benefit of the community.

The Bude Canal was unique to the UK and the world in many respects, it is worth summarising these:

The first canal and second in the world, to use water-powered incline planes with tub-boats and the most incline planes anywhere.

The well-and-bucket lift system employed at Hobbacott Downs was unique in the UK - with only one exception in the world.

It was the first and longest canal to be worked by tub-boats, which were fitted with permanent wheels - they were, in effect, amphibious craft.

Fixed wheels on tub-boats

Measured in retrospect, Trade at the Port of Bude increased considerably, trade in slate demonstrated that many new properties were built in Bude at this time. Farmland output was greatly enhanced and even today, the clay soils of farms are more manageable as a result of the grittier components of the sand. And the building of the canal was undoubtedly the spur for much of the development of the nineteenth century. The final cost of building the canal was around £126,000 (£13.6million)its value to the town of Bude today is incalculable.

Picture shows the Barge Workshop Museum at Helebridge.

A guided walk along sections of the canal will follow in due course.

Photo shows the lock near Whalesborough on your return walk to Bude. Just continue to follow the path which will bring you to the Falcon Bridge near the Tourist Information Centre

Writing this piece has been greatly helped by the research and writings of many authors. These books are available locally for those wishing to read the full story of this unique canal system. They are listed in the information menu.

You may now like to follow our Canal Guided Walk. Just click “Bude Canal Walk” below.

A further section nearer to Holsworthy, follows a canal side footpath along a four and a half mile stretch of canal owned, and preserved by, the The Canal Trust Ltd.

If you would like to support the continued development of this website please drop down to the next page.

If you enjoy reading about our history without any adverts appearing, please help me to meet all the cost with a small donation.

For extra security, the link below will take you directly to the Paypal payment centre without an intermediate stage.

For more details of how this donation will benefit you and young local people to our area, please select “info” on the menu button.

Your payment will be much appreciated, however small, thank you.