Bude Harbour Walk

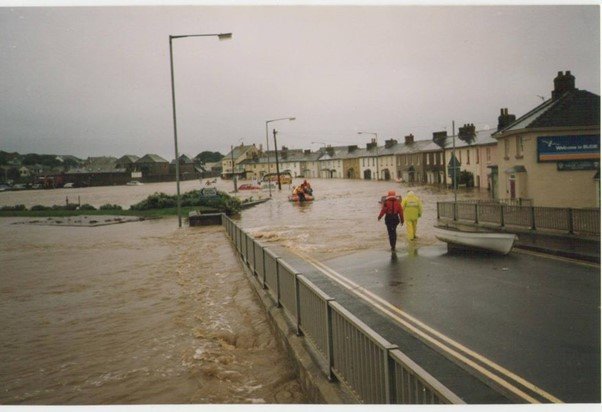

Estuary of River Neet in Flood Showing Extent of Estuary to Helebridge

Valley of River Neet: Below is the River Neet and its valley. In the early post-glacial period this was a large estuary and was navigable up to Hele Bridge, around three kilometres inland. (Shown here by digital modification). It would have been a convenient harbour for our early pre-history peoples and we know they used the harbour as they left their flint workings and later burial mounds. The valley remained navigable for many centuries until a tidal mill was built across the mouth of the harbour in c1577. This sped-up the natural process of silt accumulation.

Digital work by David Thorn from a photograph taken by Keiran Hammond.)

Find your way to the top of Belle Vue and the turning into Summerleaze Crescent. Walk along the road until the turning space outside of the Atlantic House Hotel and take up position looking down towards the river and town. The story of Bude and its harbour really starts with this valley leading to Helebridge in the distance.

Helebridge:

Historically, Helebridge was the only crossing point of the estuary. It was considered so important that it was designated as a county bridge which meant that it had to be permanently kept in good order. In Roman times it was called “Vil de Ponte”. In the volts of the Church at Marhamchurch are records that show that two men were engaged to keep the bridges and the dam between them in order for life.

The picture shows the old bridge today and on the next page is the footpath at Helebridge which follows the old causeway to the where what was called Widemouth Bridge was located- which in fact is just a few hundred metres along the path.

Battle of Hehil 722 AD: While still talking of Helebridge; in the distant past, it held a strategic location, which some have suggested was the location of the Battle of Hehil in 722AD, where the Celtic west defeated Ine of Wessex and secured Cornwall for the British for at least 150 years. The farmstead set on the hill, southwest of Hele Bridge, and acquired the Saxon name of the fortress of the Wealas (the Welsh Britons), that is Whalesborough. All villages and farmsteads to the south of this position have Cornish prefixes. There is no doubt that this was the boundary between Saxon England and Celtic Cornwall.

Pathways is the walk south from Helebridge following the high ground that was the causeway between the two bridges. The old Bude railway also passed along a section of this path.

Throughout early history the harbour would have been a safe and navigable haven for mariners. However, in 1577 Sir John Arundell of Ebbingford Manor and Trerice, decided to build a tidal mill and dam across the mouth of the estuary and this caused sand to build up both on the seaward side of the mill and on the landward side. The net result was that the harbour was no longer navigable. The image opposite shows what Bude would have looked like when the tidal mill and dam were operational.

Opposite is a painting by Harry McConville of Bude, prepared for the book, “Bude’s Tide Mill and Bridge”. (See Information, Books Available from the menu,)

Sir John died in September 1580 but his wife, Lady Gertrude, continued to run the estate and mill and built the first bridge at this location to enable packhorses to deliver corn to the mill.

It is quite possible that if the mill was not built, this whole area may have remained part of the estuary and the north and south sides of the estuary may have been permanently divided.

Division of Land: The creation of the tidal mill and dam enable the local people to cross from north to south safely for the first time, but a divide was also created between two great estates. To the immediate south were the estates of Ebbingford and the land to the north was held by the manors of the Grenvilles of Stowe -(sometimes spelt Granville) and later Thynnes.

Sir Thomas Dyke Acland inherited the family estate of Ebbingford to the south of Bude in 1808 when he “became of age”; he was young and extremely enthusiastic about his estate here in Bude and his enthusiasm and benevolent spirit was boundless.

This walk is a testament to Sir Thomas, and we will see how his youthful confidence developed the town from a sleepy village of seven houses to the point that it outgrew its parent town of Stratton. (See the Acland story and Bude Canal Walk.)

Preserving our Downlands: Continue to walk towards the sea and up to the Elizabeth Flagpole atop the downs.

It was not all plain sailing for Sir Thomas, there was opposition to his plans and financial risks. Some farmers wanted to plough the Downland. But he was advised (a little paraphrased), “if you wish to preserve the value of your investments, then you must stop tillage of the downs”. “If these lands are tilled, then you will lose all hopes of converting Bude as a watering place”. This advice related to the Downs to the south of the river but instilled in Sir Thomas that he should preserve his land for everyone to enjoy.

The Downs you are now on, and the beach below, are today called Summerleaze. More correctly they should be Summer Lease; the local people held the lease to graze their animals on the downs during the summer and when the Thynne family wanted to build a large hotel on the downs in 1887, as had happened at Newquay and Tintagel, they fought to retain their rights. Mr Thynne was not at all pleased about this and held a grudge against the people of Bude for some time, but as a consequence, Summerleaze Downs also remained free of building and open to us all.

Today you can walk around 14 miles to Hartland Quay without encountering any housing of consequence. Similarly, the 12 miles southward to Tintagel – save the encroachments at Widemouth Bay, and the village of Boscastle. Local people are very proud of, and value, this unspoilt countryside.

Wreck of the Ketch Elizabeth: The flagpole came from the 50-ton ketch Elizabeth; she had entered the harbour on February 16th, 1912 and was being warped along the harbour entrance channel in fairly heavy seas to her anchorage near the canal lock gates, when she broke free of the warping ropes. There was a strong rip current running across the beach, and this carried her on to Coach Rocks, just seaward of the present-day swimming pool.

Ladies Bathing Beach:

Before heading down to view the spot of the Elizabeth wreck, there is a wonderful account by a local lady and her bathing experience. She wrote: a Donkey takes me to the beach, and it is a bad plan to add fatigue to the exertion of bathing. A maidservant accompanies me, and the donkey-boy carries my basket, containing a bathing-dress, brush and comb, and a couple of towels. I bid adieu to the boy and donkey and being quite brave I prefers to change under cover of large rocks, but my Maid has an umbrella to protect me from peering eyes.

She goes on to say, “four or five dips beneath the waves for beginners and seven or eight dips for those more accustomed to the salt-water, is as much as is good for health”.

There were bathing tents, but they came with problems; they tended to blow open or even away completely at inopportune moments!

On the Downs was a hut in which the beach lifesaving apparatus was stored, ready for use. Mrs Anne Moore, who we will meet later, looked after the ladies on their beach at Maer Lake (now Crooklets Beach) for around twenty five years. A task taken on by her daughter Harriet Brinton, when her mother retired. Harriet, in 1888 asked the “Bude Improvement Committee” if she could use this hut to store the bathing tents; the ones that came with risk in use. But rescue was at hand as, Colonel Field had commissioned a new design of bathing machines that would save the ladies embarrassment. He asked the Committee permission to raise a flag on the flagstaff, when there was a horse available to take the machines to the beach. Harriet was given permission to use the building, so long as she locked it at the end of each day. However, the permission of Mr H. F. Thynne, who owned the Downs and flagstaff, would have to be sought - but that’s the Mr Thynne who the local people would not allow to build his hotel where you are now standing!

Now walk directly towards the sea to a white pole with a yellow diamond panel atop, you will see Coach Rocks where the Elizabeth came to grief. Look for the rocky outcrop just beyond the swimming pool.

Rocket and Lifeboat Rescue:

Distressed flares were fired, and the Life Saving Apparatus (L.S.A) crew were quickly on scene and soon joined by the Bude Lifeboat, but even though the Bude Lifeboat also arrived quickly, it was too late to save the ship, the Elizabeth became a total wreck. The photograph actually shows a rocket in flight towards the ship, as well as the lifeboat on its way; the difficulty of dropping a rope onto a ship in strong winds is clear.

As you look at the above scene, imagine a large ship being tossed around in heavy seas, and you will appreciate the considerable skill required to manoeuvre the lifeboat alongside. Somehow, the lifeboat men managed to take off the crew and two pilots, who had preferred the lifeboat to the breaches buoy route up the cliff!

Bude in 15th and 16th Century:

From the Downs, head back towards the town and down the pathway to the small bridge crossing the river, which is today called Nanny Moore’s Bridge. (See Content - Nanny Moore)

The Bede Haven story now enters the 15th and 16th Century history.

The Port of Stratton: Just to your left are a number of town houses built on what used to be the old Granville Quay - now Granville Terrace. The Quay House which still stands, set back from the others, was built in AD 1480 by Sir Thomas Granville. (See Grenville Story) The original house was built of cob and almost certainly had a thatched roof. It is much modified externally but represents the second oldest house in Bude. However, Bude, at this time was the Port Village of principal town of Stratton.

An important Harbour: Bude at this time was a busy harbour delivering goods to the neighbourhood and exporting products of Bark and Corn. But a very small population. There was a Warehouse seaward of your present position and vessels could be warped in alongside the Quay to offload and load goods. The course of the river then followed a straight line, from Nanny Moore’s Bridge, past this Warehouse, and out to sea where the open-air swimming pool is now. The river was changed to its present course past the lock gates to help keep the harbour entrance free of sand. There were no roads of any significance in this part, or in fact many parts, of Cornwall until the 19th Century, all transport was by sea and then to packhorses.

This image is taken from the Joseph Stannard painting of 1832 (shown in full later) as it shows the sand laden packhorses and also a ship loading or unloading cargo in the Granville Quay - that is just behind the man in the red waistcoat. It is just possible to see hoppers used to channel corn or similar produce straight into the hull of the vessel. This is where the Grenville Garages are today - just behind you.

Early Watering - bathing and drinking!

To your right is the old bridge now called Nanny Moore’s bridge and cottages. It is named after the lady who lived in the first cottage in the early 19th century, and it was she who “Nanny’d” or supervised the ladies on the ladies bathing Beach at Maer Lake (Crooklets Beach) - until she retired with ill health, probably around 1848. The cottages are built on the foundations of a 16th century tidal Gristmill. Nearby and possibly near to Granville Quay House was Bude’s first Pub, “The Sailor Boys”. Certainly there was a brew house recorded here around this time.

Tidal Grist Mill: Around 1577, Sir John and Lady Gertrude Arundell, who lived on the southside of the harbour at Ebbingford Manor, built the tidal grist mill and a large dam and sluice system which impounded a reservoir of seawater, to power the mill when the tide had ebbed. The crossing of the river and estuary had been precarious, as it was deeper and much wider than today, especially as the tide rose. Now the local people used the dam walls as a causeway. Unfortunately, Sir John died a few years later on 15th September 1580, but for the people of Port village, the causeway was a saviour. The feudal laws introduce in Norman Times stipulated that corn grown on the Lord of the Manor’s land should be milled at his mills. This was known as, “Milling Spoke”.

The picture shows part of the sluice gate that accepted sea water into the dam. The water was released through the mill workings when the tide had receded.

Sir Richard Carew, at around 1577, was writing his famous book “The Survey of Cornwall” in it he says, that the area to the south of the river is called Ebbing-ford, but that it should now change its name as, “Master Arundell of Trerice, who has a pleasant seated house here, has “builded a salt-water mill athwart this bay, whose causeway serveth as a very convenient bridge to save the way of the farer’s former trouble, let and danger”. Sir Richard Carew was the son-in-law of Sir John Arundell, having married Sir John’s daughter Juliana - by his first wife - in 1577. His Survey of Cornwall was eventually published in 1602 after many years of delay.

(In fact, the river was initially crossed by stepping stones, further upstream, where is was wider and shallower. The stepping stones led to the dam causeway referred to by Carew.)

Lady Gertrude Arundel was Sir john’s second wife and upon his death in 1580, she built the first simple crossing here to allow packhorses to deliver corn to the mill. Later, in the eighteenth century a three-arched bridge was built - this was known, eventually, as the Old Bridge. Finally, in around 1860 the bridge you see today was built. This is Nanny Moore’s Bridge.

From 1480 the Granville family of Stowe built Granville Quay on the northside of the bridge to export bark to the tannin works of Ireland. The final section of the bridge had a wooden section that could be raised to allow small boats to pass to the inner harbour.

The picture opposite is displayed in the Castle Heritage Centre and shows the “Old Bridge”. It is not an accurate representation. It is really an image of the bridge around 1845. The wooden section, near the cottages, shows bathing suits hanging out to dry; these were available for ladies to use by Nanny Moore.

The bridge itself has taken many forms since first building by Lady Gertrude in 1580. It played an important part in protecting the Royalist encampment on the south downs at the time of the Civil War in May 1643. The high evening tide mean that the Parliamentarians on the north side of the harbour could not cross with safety and a standoff was forced until very early morning. At that time the crossing here was described simply as a “pass”.

The Stone Mystery: After the death of her husband in 1580, Lady Gertrude had a large block of granite carved with the initials AJA 1589. And set into the mill or dam structure. The reason for this has always been unclear and it was initially thought to indicate the build date of the mill. The carving has the “Three Hatchet” Coat-of-Arms of her own family, the Denys – not the Arundell, plus, the letters “AJA” and the date 1859.

Some writers have proposed the letters relates to two of her own, Arundel children, Anne and John, but they had four surviving children. The footnote below offers an alternative explanation -suggesting this mix of Coat-of-Arms and initials was a convenient and, ambiguous way, of remembering a family member who died for their faith - but could be interpreted as relating to her own children if the need arose? We do not know.

The 1550’s was, as someone wrote in the 1890’s, “one of the most important periods of our national history- and stirring events then taking place were regarded with interest by our North Cornwall worthies”. This person was alluding to the Reformation and the persecution of Catholics and the Arundell family were Recusants in this respect. Family members were friendly with Martyrs such as Cuthbert Mayne. Another John Arundell had been imprisoned for seven years for his support of another Recusant, John Cornelius. This John Arundell was eventually released, but died shortly after in, it is said, 1589. His wife was an Ann.

Period of Significant Growth: In the late 18th century the little “Village” of Bude was developing. Two warehouses were built by Mr Bray around 1780, to support his trade in “coal and general import and corn export”. These were built behind Hartland Terrace, that is roughly where the present-day Main Post Office is situated. By 1825, 151 Ships are thought to be traded out of the village. Population around 700.

Mr Bray’s warehouse was knocked down; this is a later Corn Store.

The Inner Harbour: Now walk towards the town to an area near the bus stop. At this point in the early 19th century, horse and carts waded through the water to the south bank, as this was the only way to cross the river.

A little further upstream from your present position, there was a further quay or jetty where small barges took the goods that had been unloaded from the larger vessels in the bay, to a warehouse located next to the Carrier’s Inn.

This Harry Thorn photograph shows the jetty and warehouses.

To your left is the modern TSB (Bank). This is where in 1780’s the “Bewd Inn was built, later the Bude Hotel. To the right of the Hotel, where today there is a mini-roundabout, the Hotel had its stables.

In 1775 The Villa, located up the little passageway ahead of you, was built by a Mr John Arscott of Tetcott as a summer residence. It is today a Veterinary Practice.

A grass slope led from the Villa to a green gate, located at today’s street level and, the high tides regularly deposited seaweed and other flotsam under the gate - as it did to the door of the Bewd Inn.

Summer Visitors:

Within ten years, Bude was beginning to attract other visitors for summer bathing. Two or three families in 1798 came from Launceston (16 miles) to spend August bathing. They were accommodated in room above the shops to the right of this picture. In 1802 Sir Thomas Acland will inherit the former Arundel Estates and the impetus and confidence that he will bring to Bude will be the spur for further development.

Back to Nanny Moore’s Bridge: Cross the bridge and remember to look at the granite block, with the carved letters AJA and 1589, embedded in the forecourt of Leven Cottages.

However, the image opposite is digitally changed to show the mill and mill dam as it was in the 16th century. The bridge has been removed to show the outlet from the mill at the river’s edge where it was kept clear of sand by the river flow.

(Digital work by David Thorn from an early 1860’s photograph taken by Harry Thorn.)

Today, you have the Sports Ground Sports Ground on your right followed by the entrance to the Castle. You are now walking on what was the original dam wall. However, this was dismantled to build part of the modern day Leven Cottages, that you have just passed and, the crossing here became precarious once again.

A Forgotten Genius: In front of you is the Castle built by Sir Goldsworthy Gurney in 1830. He is considered by Bude people as “Bude’s Forgotten Genius”.

He was a Cornish Doctor, a pioneer, scientist, engineer and inventor. He invented the Bude (lime) light. He installed the light in his house; a single Bude light source was used with mirrors placed such that all rooms were lit by reflection. He thought this system of mirrors could be used to light mine underground workings, negating the risk of naked-flame explosions as the Bude Light remained on the surface.

The Bude light was also installed in many fashionable locations in London and, in the House of Commons, where three Lights replaced 280 candles. He also proposed a Bude Light on a revolving base with sequenced flashes for use in lighthouses, again using mirrors (1864). (Contents Menu Gurney)

Steam Road Transport: Gurney also invented many other devices including a steam carriage that ran between London and Bath, plus various steam and heating systems. There was much opposition to the carriage, supposedly as it frightened the horses generally, but more probably because it negated the use of horses, regular stops at Inns and all that went with that.

Home Built on Sand:

This is an early impression of the Castle and even in the building of his house in 1830 Sir Gurney demonstration modern invention, in that the whole building is mounted on nothing more than a pile of sand – but mounted on a platform of reinforced concrete.

In the 1860’s the house was owned by William Maskell and it later became the Council Offices and it presently houses the Bude Heritage Centre.

Gurney built his house on concrete in 1830. Portland Cement had been invented just six years earlier in 1824 by Joseph Aspdin. His cement when mixed with an aggregate of sand, or gravel, and water was considered, “a strong binding agent, predictable in its behaviour and of a consistently high quality”. As far as is known, this is the first house to have been built in this way. Brunel and others would follow in the years to come.

A Precarious Crossing:

The path you have just taken from Nanny Moore’s Bridge was a precarious passage across a tidal estuary for hundreds of years. When the Gristmill was built in c1577, the mill dam offered a raised causeway.

In the 19th century the dam was dismantled and the stones used to build an extra cottage and a series of stepping stones, just visible in this image - described as the pontoon bridge. It is possible that at this time, the Sailor Boys Inn became a Pastry Shop owned by a Mr Cobbledick.

The removal of the millpond dam opened the area to the full force of the sea and this quickly removed any vestige of the millpond and the sand hills known today as Shalder Hills were soon formed. It is a miracle that the cottages survived this onslaught, isolated and unprotected as they were.

Image courtesy of the Keats family of Bude.

The First School: Just behind you now are the grounds of the old schoolhouse. This was built by Sir Thomas in 1849, but subsequently enlarged. Sir Thomas and Lady Acland were strongly in favour of providing education for children of all classes of society and had already built schools at their other estates at Killerton and Holnicote. However, to accommodate the enlargement of the school and its grounds, part of the East Shalder Hill had to be removed.

Today the buildings are a complex of meeting rooms, theatre Hall and Council Offices.

The Bark House: Walk towards the canal and fire station; around 25 metres to your left you will find “The Kitchen Front”.

This was the old Bark House. Although just a small village of six or seven houses, Bude was a busy trading Port for the principal Town of Stratton in the 17th and 18th century. Large quantities of corn were exported, and Oak tree-bark was harvested during March when the sap was at its strongest; the process was called Rhinding, that is stripped tubes of bark from the lower part of the tree. The bark was transported to this building by packhorse and shipped to Ireland where it was used to produce tannin for leather making. The returning ships probably collected Coal, Limestone and salt from Bristol and Wales. Salt was made locally but large quantities were used to preserve fish for winter consumption in the nearby fish cellars.

The Forge Buildings: Now head seaward, past the boathouse and soon on your right is a building with a number of craft shops. More recently this was the Bude Museum, but initially it was the workshop, or forge, that supported the tub-boats and the horses that towed the boats along the towpath. Fred Staddon ran the forge and farrier services, plus repairing all the iron work; George Bickle did the leather work – bridles for the horses etc – and Sab Curtis made the wagons and wheels. The story of the Canal is covered in a separate walk.

As you stand here, reflect on the fact that in 1818 you would have not been able to do so as the West Shalder Hill covered most of the area, probably to the Falcon Bridge. Shalder Hill actually does mean, the hill that is blocking the valley and river flow. The blown sand was a valuable product used to sweeten the clay soils of the local farmlands - blown sand had more shell material than the wet sand.

Some 200M beyond the present Falcon bridge there were basic houses, or hovels, for some of the local labourers- the sandhills gave shelter from the westerly winds. Later this would become the Seamen’s Shelter and in more recent times the Scout Hut.

Now walk towards the lock gates. As you cross the Lock Gates, to your upper left is a small rather pointed house. This was once the Rocket House. It was used to store the rocket Life-Saving Apparatus (L.S.A.) that played such an important role in saving countless lives along our shores.

On your left back 25 yards was the original Lifeboat House which also housed the Life-Saving Apparatus (L.S.A.) that played such an important role in saving countless lives along our shores. Built in 1836/7 to house the first Lifeboat, it is the one with double doors on the front. It was given to Bude by King William IV. The Lifeboat was launched in to the canal opposite or taken down to the beach if the tide was out. After 1863 when a second Lifeboat House was built it was the base for the Coastguards.

The idea of a rocket launched rescue system had been conceived by others, but the idea was developed for effective use by Mr Trengrouse of Helston. His rocket carried a line to the stricken vessel which then enabled other devices to be drawn to the boat. Although the L.S.A. was invented in the early 1820’s it is possible that it was the 1852’s before it was in use in Bude. At this time, there were 120 stations throughout Britain using this system.

To the right of the Rocket House are East and West Cottages, seen in this photograph before the building of the Rocket House. This was a summer home for the family of Sir Thomas and Lady Acland in 1832. It was designed Sir Thomas’ architect fried, George Wightwick; the cottages were built on the site of the of Lime Kilns.

A little further on towards the sea and tucked into the cliff edge is what we call locally, the Pink House, but should really be called, Efford Cottage. This was rebuilt in 1832 around a former cottage, seen here, that was in a rather dilapidated state, even though it had been renovated earlier. It had a rather endearing name however, “Joy Cottage”.

Joy Cottage was eventually enlarged and became and served as a summer home for Sir Thomas Dyke Acland from 1832. Efford Cottage was also designed by George Wightwick.

This was at the close of the Napoleonic Wars and not the time for the aristocracy to holiday in France or Europe as had been the practice. Sir Thomas decided that Bude would be a safer option.

This picture, taken 1885, shows East and West Cottages, plus Efford Cottage and, the rather imposing Efford Down House built around 1848. The land for Efford Down House had been given to Agnes, the daughter of Sir Thomas and Lady Acland, and her husband Arthur Mills, M.P. for Taunton and Exeter on the occasion of the marriage.

It is probable that the next building added to the left of this scene would be the Rocket House, at around 1852.

Now follow around the path between the properties and walk up the steps to the start of the pathway. Immediately to the left as you reach the top step is an iron triangular marker set in the ground with the letter “A” for Acland on one face and “M”, for Mills embossed on the other. This shows the boundary of the land on the Downs given to Agnes and her husband, Arthur Mills by Sir Thomas Acland

Walk along the sea path until you have a good view of the Breakwater.

A breakwater protecting boats within the harbour was seen as essential to the viability of Bude as a Port. (See Canal Walk). However, the first breakwater was designed as a rather upright structure with a banjo peer. There were 340 men engaged in building the breakwater and lock gates on 22nd October 1820. The work was completed in 1823. But a storm on 24th and 25th of February 1838 destroyed the structure and the breakwater you now see was built in 1839. The plans for the new structure, opposite, shows how the structure had a more rounded profile and is in fact, 1.25 metres lower than the original. The larger waves now crash over the top of the structure at high tides.

The picture of the first breakwater shows how the Banjo Pier has cut into the rock outcrop. This is Chapel Rock, on the top of which was the Chapel of St Michael, a medieval hermitage on which the Bede of Bede’s Haven held his prayers or bedes. It is said that he also guided ships into the estuary by lighting faggots of wood in a barrel- perhaps the reason for Barrel Rock today.

When Richard Carew was writing his Survey of Cornwall in the late 16th century he wrote of this Bede’s Haven, “in whose mouth riseth a little hill, by every sea-flood made an island, and thereon a decayed chapel. It spareth road only to such small shipping as bring their tide with them, and leaveth them dry when the tide hath carried away the salt water”.

You may wonder just how the heavy stones used in the construction of the breakwater were transported across this difficult rocky terrain. The workmen actually dragged individual stones across the beach to the base of a ramp, perhaps visible below you from where a “Cornish Whim Engine hauled the stones up the slope. This, basically, was a horse powered winch mechanism that dragged the stones along a prepared ramp to a more manageable position at the construction site. The illustration shows one working a well, but the principals were the same for tugging the stones, horizontally.

You may like to walk to the end of the breakwater on another day where you will find “Tommy’s Pit” the swimming pool built by Sir Thomas Acland for the gentlemen. Remember that the ladies bathing was at Maer Lake, (Crooklets Beach.)

Now continue your walk by heading 100 metres south up and along the cliff path to Compass Point, or the Storm Tower, -more correctly the Temple of the Winds. This was essentially a Folly built by Sir Thomas in 1830 and based on the Tower of the Winds, Athens (c48 B.C.).

Unfortunately, coastal erosion is high here, at around 10 cm per year, and 50 years later it had to be rebuilt further away from the cliff-edge – a process, incidentally, that is now scheduled for a repeat!

The Tower did serve a function, however, to provide shelter to the coastguards manning the lookout. One individual was called the “Tide Waiter” and his role was to haul a red flag when entry to the Port was prohibited. Within the tower is a “Meridian line” from which 12 o’clock by the sun could be obtained and this was later used to monitor tide heights and times. (See Canal Story.)

Since its original building it has been moved twice further inland due to coastal erosion. The most recent move completed February 2024.

We now return towards the town and the Efford Cottage (The Pink House). As you come down the steps, on your right is a narrow lane called Church Path. This lane during World War 11 was enlarged to accommodate the heavy tanks, guns and vehicles of the American Rangers, who fired their guns seaward from the Storm Tower, as part of their training in preparation for the D-Day Landings of June 1944.

Continue the walk for ½ kilometre, on your present side of the canal, away from the sea to the Falcon Hotel. It too was built by Sir Thomas Acland in 1826 and, over the next two years, the small cottages to the left were also built. The Hotel was built on the grounds of a much older hostelry and there are records dated 1810 of rent being paid to the Aclands.

The Royal Cornwall Gazette, September 1st, 1826, writes of the rising celebrity of Bude as a watering place. “Upwards of hundred persons of fashion and valetudinarians have visited the place, especially since the reopening of the Falcon Hotel under the patronage of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland- the air being found to be salubrious and beneficial to health”. In case you are wondering, valetudinarians are people unduly anxious about their health.

The Falcon hotel seen here with its array of coaches bringing guests from the rail station and possibly departing to other destinations to north and south.

Incidentally, the hotel takes its name from the Crest or Coat-of-Arms of the Acland’s, which has a Falcon atop the head armour.

Now move to the Falcon Bridge which has undergone three incarnations. The first bridge was built in 1820 to permit passage over the canal. It had twin swing sections of wood to allow passage of ships to the upper basin. It was redesigned in 1887 with a single swing bridge of steel. The present bridge was built in 1960 and no longer permits visiting ships to pass to the upper basin.

(Picture by Harry McConville showing the trading vessel Alford passing into the Upper “Private Wharf” via the Swing bridge. Picture courtesy of Jeremy White.)

Situated on the righthand side of the bridge is an unusual little house nestled today beyond a large conifer. This is the second Lifeboat House, built in 1863, on land given to the town by Sir Thomas Acland.

The story of the Lifeboats at Bude is one of incredible skill and bravery, in boats that were simply not adequate to meet the challenges that prevailed. Anyone who has attempted to come alongside a large boat being tossed around in waves, will appreciate the difficulties and dangers. Not to mention all the logistics involved with such an operation.

Within Bude Bay there were wrecks at least every few years and the total over the centuries total many hundreds. Between Trevose Head and Lundy Island is the vast Bude Bay. Add to the mix strong tidal currents, influenced by the Bristol Channel, and strong unpredictable westerly winds. The large sailing ships were unable to sail close to, or into the wind. Once in the clutches of the Bay, they were doomed. It is not without justification that we have the grim old couplet, so well-known to the mariners of old:

From Padstow Point to Lundy Light,

Is a water grave by day or night.

The story of the Lifeboats of Bude are told in a separate article. (See Lifeboats) Sufficient to say here that there were six lifeboats between 1817 and 1923, each powered by between 8 and 10 oarsmen and pulled to the scene of the drama by a team of up to 10 horses. If the tide was in, the lifeboat could be launched into the canal, but of course, half of any day at least, this is not practical and if the rescue was needed at a remote cove, then the problems were compounded.

This photograph opposite demonstrates graphically the logistics that would be needed to manoeuvre this tonnage up and down hills and across sand dunes.

While still on the bridge you can now imagine the spectacle of a fully laden steam train crossing the road here as it delivered coal to the Coal Yards – today accommodating the Olive Tree Restaurant and the other outlets.

(On another day you can walk along the north side of the canal and follow the cycle track this will take you along the old rail line and iron bridge that led to the Rail Station and Gasworks.)

No need to look out for crossing trains today as you follow the curved road of the Crescent.

Following the completion of the canal in 1826, there was a major problem, how to cross the River Neet, which at that time, had a ford crossing to the Strand Farm on the other side of the river - what was termed “the old Bude Village”. The actual plans shown here, also involved the straightening of the course of the river to speed up the flow and avoid flooding.

The “New Bridge” was built in the early 1830’s and this replaced the old ford that crossed to a farm on the corner of the Strand. It will be seen that the design of the bridge did not allow for heavy water flow, and this caused frequent floods.

This very early Thorn Photo shows the old farm at the corner of the Stand, opposite the bridge. This was Petherick’s Farm and Manure Stores. On the left are the Corn Stores.

A Toll was charged to use the new bridge and the first house built was a tollhouse. The Thorn family lived in this house and administered the toll and, unofficially, it became known as “Thorn’s Bridge”.

The houses you see today along the Crescent were built in stages between the years 1838/9. Originally called New Buildings, then Shalder Terrace, the South Terrace before being finally given the more fashionable name of, The Crescent. (See Thorn Family Story.) Today the bridge is called Bencoolen Bridge, named after another famous shipwreck in the harbour, but it too has undergone two further re-builds; (1960 and 2014/15.)

That unfortunately was not the end of the flooding story for the Crescent and its residents, as it continued to regularly flood and, unfortunately still does, as shown in this 1993 event. However, in 1888 it was decided to build and embankment from the Bencoolen Bridge to Helebridge to alleviate this problem. The necessary funds were to be raised by public subscription. However, one of the dignitaries, who could afford to contribute was Mr Thynne, who initially declined, “on account of the Summerleaze question”. He did eventually contribute £10. And, in 1890 the embankment was lengthened to incorporate the section to Nanny Moore’s bridge.

As you cross the Bencoolen bridge of today turn to walk along the Strand. Here we can show one of the earliest Thorn photographs of Bude. It shows the Hockin and Hooper Corn Stores with masses of timber on the banks of the river to your left. The Stores were located on your right as you walk along this section.

Continue your walk along the Strand the Strand. This takes you to the Carriers Inn; itself a very old building.

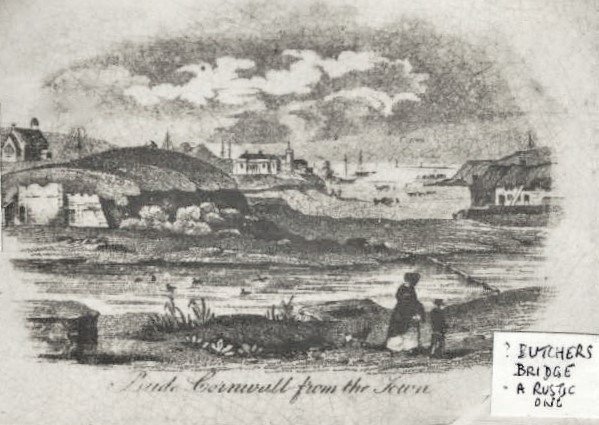

This was also where a rustic steppingstone pontoon, called “Butcher’s Bridge” crossed the river to Shalder Hills and to what was possibly lime kilns. Local people in 1890 wanted this rebuilt as it was more convenient than the bridge!

The colour image shows a similar steppingstone bridge in use today. It is in the Carew River area of Pembrokeshire, South Wales.

As you near the end of your walk, look to your left where you can see the remaining Shalder Hill on which is placed the War Memorial and on which the town has a Weather Station, which has faithfully been run by local people for much of the last century. As a result, the weather stats tell us that Bude does enjoy a special climate when compared to many west coast resorts.

To your right is the Globe Hotel, this was originally “The Canal Inn” built at the same time as the canal itself (1819 to 1826). The Publican was a lady affectionately known as Nanny Wilson. It almost certainly initially cashed in on the cash available from the hundreds of men working on the canal itself and from the many men now involved in the busy Port. In the picture you may be able to discern the name “Globe”. That’s the white building on the right.

Mr Thynne did eventually get permission to build a hotel, “away from the Downs”. In 1908 he commenced to build the Grenville Hotel, which was completed in 1912. After clearing yet another very big hill of sand and, eventually, dismantling the row of cottages called Marine Terrace seen in this picture.

But the Bude people had not ended their desire to fight any plans that took away their rights to open space. When Queen Street was being built next to “the Commons” the builders put up a fence on one day, only to find it removed the next!!

In very recent times, a Planning Committee wanted to change the nature of, “The Triangle” at the centre of town. Needless to say, this too caused ruffled feathers and has yet to be resolved. We are all proud that we now have a Golf Course, Nature Reserve and Open Downs plus, of course, our beaches surrounding us, and the Canal and River running through the town.

This is the early story of the Harbour of Bude; we chose the term Harbour Walk, as it was the need to secure a harbour for the Canal that led to the development of the town we know today. This was largely due to the drive and enthusiasm of one man, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland. The advice he received, that he should preserve the Downs to secure his investments for everyone to “take the fresh air” has left us all with a unique resort, where the coastline and country is as open as nature intended.